Hi 👋 - Happy Thanksgiving. Pumpkin pie got the better of me this week, so dipping into the archives to look at Minsky Moments, the idea that periods of economic stability lead to instability. Next week, will be an autopsy on bed-in-a-box company Casper. As always, thanks for reading.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers. 🦃

The Hand That Feeds You

Calm seas can be deceiving. There are limits to what can be learned from observation alone. In The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable, statistician and former derivatives trader Nassim Nicholas Taleb illustrates this point with a turkey. Every day, the turkey is fed by a farmer. With each meal, the turkey’s confidence grows that the farmer is looking out for his best interest. On the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, there’s a nasty surprise:

The hand that feeds you may have ulterior motives. Speaking to the danger of extrapolation, Taleb writes:

What can a turkey learn about what is in store for it tomorrow from the events of yesterday? A lot, perhaps, but certainly a little less than it thinks, and it is that “little less” that makes all the difference.

Minsky Moments

The turkey feels the safest right before he heads off to the butcher. Its confidence and its risk rise in tandem. This setup wouldn't feel foreign to Hyman Minsky, a mid-twentieth-century American economist who studied financial crises.

During his lifetime, Minsky’s theories collected dust. He passed away in 1996 a relatively obscure economist. This changed in the fall of 2007 amid the subprime mortgage meltdown and subsequent financial crisis. Today, Minsky is best known for his Financial Instability Hypothesis. The hypothesis asserts that periods of prosperity sow the seeds of the next crisis. Stability begets instability.

Minsky saw booms and busts as an inevitable part of a market economy. During economic expansions, he believed that borrowers - companies, consumers, and investors - took on riskier debts as asset prices increased. When the music stopped playing, the process reversed, resulting in a financial crisis.

More specifically, Minsky identified three types of financing:

Hedge financing: Borrowers can repay their debt with future cash flows. This is the safest form of financing.

Speculative financing: Borrowers can pay the interest on their debt, but not the principal. As such, they need to roll over their loans. This works when the economy is growing, asset prices are increasing, and capital markets are functioning smoothly. It is a riskier form of financing.

Ponzi financing: Borrowers cannot afford to cover their interest or principal. The borrower is betting that the underlying asset will increase in price and is relying on this to repay their debt. This is the riskiest form of financing.

Minsky posited that when hedge financing dominates, the economy is stable. As speculative and Ponzi financing increase, so too does the risk of a financial crisis.

Human nature, profit seeking, short memories, and a host of other factors mean that when times are good, people take more risk. During these periods, speculative and Ponzi financing grow. As former Citi CEO Chuck Prince notoriously quipped, “As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance.” There’s the rub.

Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis is kind of like a hangover. Let’s say you’ve had one or two drinks and are feeling good. You should probably order a club soda next, but music is bumping, your jokes are landing, and you’re starting to feel like the guy in the Dos Equis ads. So you have a few more drinks. At some point, you cross a line and the consequence is a nasty hangover in the morning. Too much of a good time can get you into trouble.

Home Prices Move In Two Directions

Paul McCulley, former chief economist of asset manager PIMCO, maps Minsky’s theory to the real world in his excellent synopsis of the 2008 financial crisis:

Hedge financing: Traditional mortgages where the borrower could afford to pay both the principal and the interest on the loan.

Speculative financing: Interest-only mortgages. The borrower could afford to pay the interest, but not the principal. This required the mortgage to be refinanced. As long as home values were climbing, this wasn't an issue.

Ponzi financing: A negative amortization loan where the principal increases over time. Borrowers could not afford to make the full interest payment. However, lenders would underwrite these loans because they believed home prices would continue to increase.

Lots of mortgages were made on the assumption that housing prices would continue to go up. A rosy outlook led people to take on more and riskier forms of debt, sowing the seeds of a financial crisis. This is the Financial Instability Hypothesis in action. McCulley writes that:

The essence of the Hypothesis is that stability is destabilizing because capitalists have a herding tendency to extrapolate stability into infinity, putting in place ever-more risky debt structures, up to and including Ponzi units, that undermine stability.

At some point, the music stops playing. Always.

Things started to fall apart in late 2007 when rising housing prices hit the wall of housing affordability, what McCulley dubs a “Minsky Moment.” With prices no longer climbing, Ponzi borrowers were underwater, with some forced to sell or foreclose on their homes. This put downward pressure on housing prices, meaning that speculative borrowers could no longer rollover their mortgages. This led to more selling and foreclosures and a downward spiral that torched some hedge borrowers and precipitated a financial crisis.

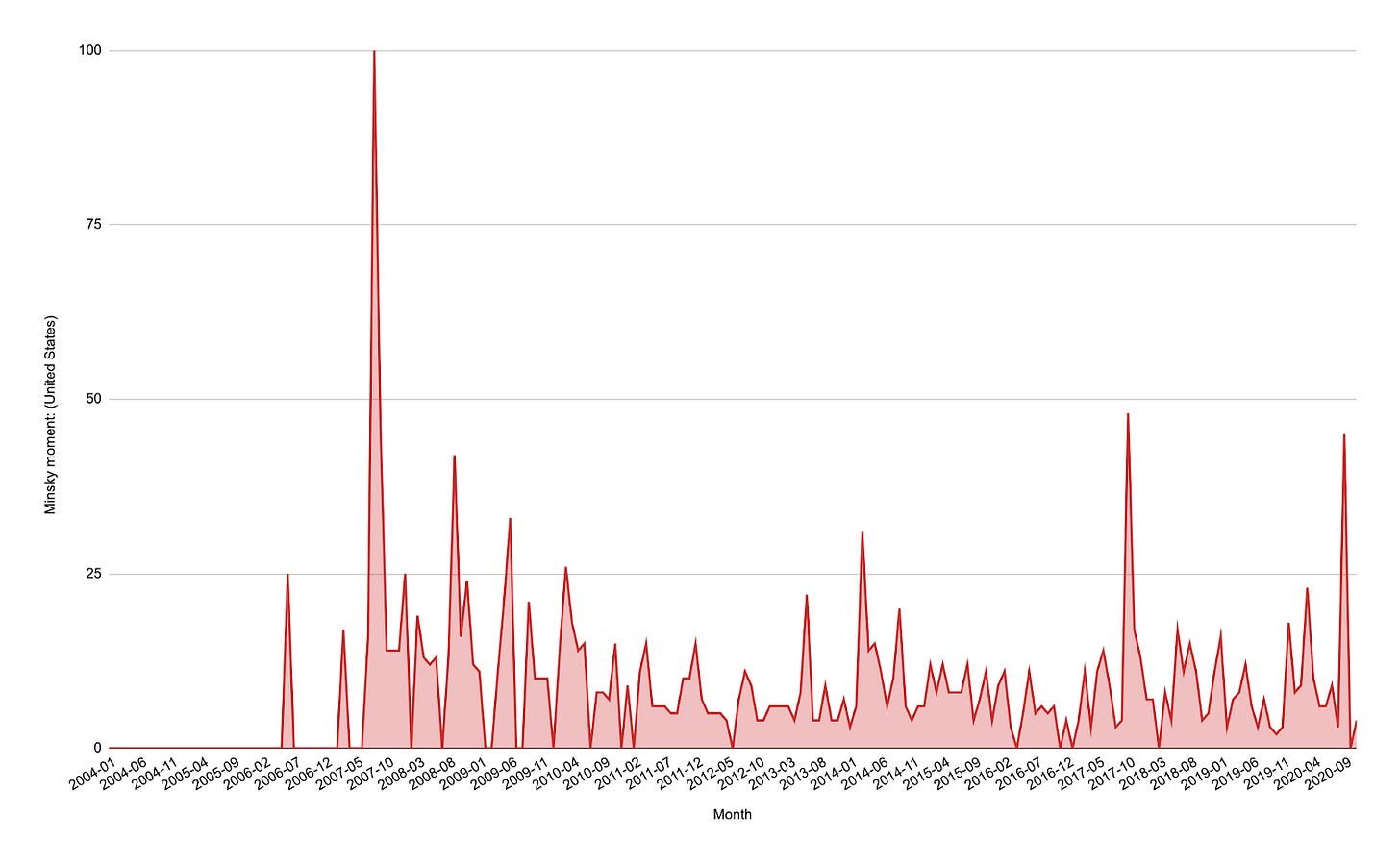

The chart below shows Google searches for “Minsky moment.” It’s the mirror image of the turkey’s history. A period of calm abruptly punctuated by a spike in October 2007 at the start of the financial crisis. As the turkey learned the day before Thanksgiving, stability can breed instability.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers. 🦃

For more like this once a week, consider subscribing. 🦃

More Good Reads

Nassim Nicholas Taleb on debt, risk, and skin in the game. The Economist on Minsky moments.