Though easy to forget, predicting the future is hard.

While outcomes appear black and white, victory or defeat for instance, the path there is often anything but. If a butterfly had flapped its wings differently, the end result could be very different. This uncertainty makes precise forecasts dangerous.

How Not to Communicate a Forecast

Because forecasts are uncertain, it’s important not to communicate them with certainty.

In April 1997, the Red River flooded parts of North Dakota and Minnesota. The flood caused extensive damage in Grand Forks, North Dakota, destroying or damaging 75% of homes, displacing nearly 50,000 residents, and costing over $3 billion to clean up. As statistician and FiverThirtyEight founder Nate Silver recounts in The Signal and the Noise, what makes the disaster more tragic is that it might have been preventable.

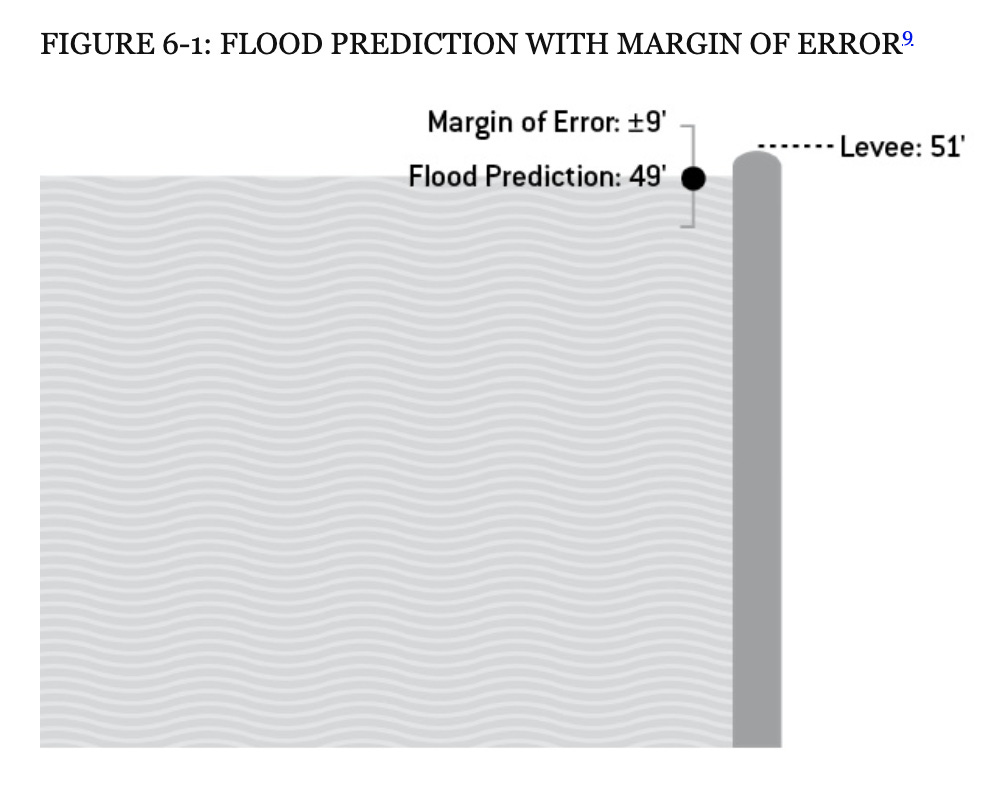

Because of heavy snow that winter, the National Weather Service and Grand Forks residents were alert to the risk of flooding. In early 1997, the National Weather Service predicted that the Red River would crest at 49 feet. The levees in Grand Forks were built to withstand a 51 foot swell, so things seemed alright. Ultimately, the river peaked at 54 feet, overwhelming the levees and wreaking the city.

As Silver points out, the National Weather Service made a crucial omission in communicating their forecast: the 49 foot crest prediction had a margin of error of plus or minus nine feet. Not wanting the public to lose faith in their forecasts, the Weather Service intentionally kept this information to themselves.

This highlights the danger of putting too much faith in a point forecast. The 49 foot crest prediction created a false sense of confidence. Incorporating the margin of error, the crest could have been anywhere from 40 feet to 58 feet meaning there was always a chance that the levees wouldn’t hold. Had residents felt more at risk, they might have reinforced the levees or tried diverting waters to less populated areas.

The National Weather Service now communicates uncertainty in their forecasts by including a margin of error, but many forecasters don’t.

The Central Concept of Investing

In The Intelligent Investor, value investing OG Benjamin Graham refers to a margin of safety as “the central concept of investing.” In Graham’s parlance, a margin of safety means buying a security at a market price far below intrinsic value. In layman's terms, it means the buyer is getting a good deal.

If you think an asset is worth $100 and you can buy it for $75, you’ve got a margin of safety. If you can buy that same asset for $50, you’ve got a bigger one. Even if the asset is worth less than $100, you’ve got a cushion.

Graham insisted on a margin of safety for the same reason that Silver insists on communicating uncertainty with forecasts: it’s impossible to predict the future. As Graham writes in The Intelligent Investor:

The function of the margin of safety is, in essence, of rendering unnecessary an accurate estimate of the future.

In another nod to reality, Graham approached investing probabilistically, considering an investment’s risk-reward ratio. He understood that the juiciest looking investments could still end up losing money:

Even with a margin in the investor’s favor, an individual security may work out badly. For the margin guarantees only that he has a better chance for profit than for loss - not that loss is impossible.

Graham’s margin of safety is the investing equivalent of the National Weather Service’s margin of error.

The Needle Went Down to Georgia

Presenting a forecast as a range of values instead of just one value helps account for uncertainty. The New York Times’ election needles are a good example. While the needles presented a point forecast at any given time - say a 65% probability of Biden winning in Georgia or a 98% chance of a Trump victory in Florida - they also included a range of estimates, reflecting uncertainty. For a close race like Georgia, this showed that either candidate winning was a possibility.

Premortems are another tool for reflecting uncertainty. A premortem is a brainstorming session that happens before a project is complete. It presupposes a disastrous outcome and asks each group member to identify what might have caused the disaster. In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Nobel Prize-winning economics and Below the Line crush Daniel Kahneman writes that:

The main virtue of the premortem is that it legitimizes doubts. Furthermore, it encourages even supporters of the decision to search for possible threats that they had not considered earlier.

A good forecast should reflect uncertainty. Sometimes when you’re expecting the Four Seasons, you get Four Seasons Total Landscaping.

For more like this once a week, consider subscribing 👇

👉 If you enjoyed reading this post, please share it with friends!