In 2003, rapper 50 Cent released Get Rich or Die Tryin’. Featuring hits like “In da Club” and “21 Questions,” the album was a commercial and critical success. But Get Rich or Die Tryin’ isn’t just a great album, it’s also a good way to describe the attitude of many entrepreneurs and investors.

Entrepreneurs want to grow companies. Venture capitalists want to identify companies posed to grow. Both are well served by large markets. Here’s how Aswath Damodaran, Professor of Finance at New York University, describes it in his blog post The Market is Huge!:

There is nothing more exciting for a nascent business than the perceived presence of a big market for its products and services, and the attraction is easy to understand. In the minds of entrepreneurs in these markets, big markets offer the promise of easily scalable revenues, which if coupled with profitability, can translate into large profits and high valuations.

You don’t need to look hard to find examples of this. Here’s a recent one from Techcrunch:

It’s a huge market to chase after. Though there’s an assortment of (huge) estimates out there, Roofstock pegs the single-family rental market at a whopping $3 trillion. Investors just gave the company a fresh $50 million to go after it more aggressively.

Huge market. Huge!

Capturing just one percent of this $3 trillion market would equate to $30 billion in revenue. You can see why someone would be excited about that. That’ll buy you a lot of Teslas.

Alas, when it comes to numbers, reality is much harsher than spreadsheet math.

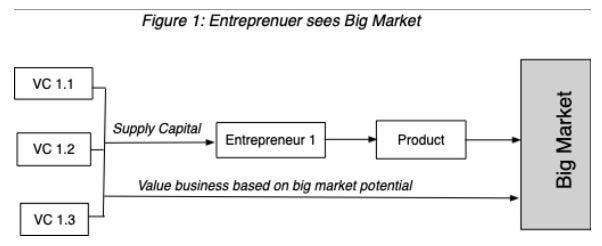

Turning to Professor Damodaran’s paper, The Big Market Delusion: Valuation and Investment Implications, big markets typically aren’t proprietary. The opportunity that one entrepreneur sees is likely to be seen by others as well. Same with investors. So instead of a situation like this:

Source: Aswath Damodaran, The Big Market Delusion: Valuation and Investment Implications

Reality looks more like this:

Source: Aswath Damodaran, The Big Market Delusion: Valuation and Investment Implications

This is where things start to get spicy.

Large markets attract lots of competition and lots of capital. Professor Damodaran argues that this situation is exacerbated by overconfidence, the:

tendency of individuals to overestimate the quality of information they receive, their ability to analyze that information, and their capability of using that information to influence future outcomes.

There’s no shortage of overconfidence among entrepreneurs and venture capitalists. Everyone thinks that they can pick the winner. But not everyone can win. The result can be collective irrationality, or what Professor Damodaran calls the big market delusion:

Businesses that are targeting the big market will be collectively overpriced, since each cluster is convinced that will be the winner…The market will become more crowded and competitive over time with new entrants being drawn in because of the perceived growth potential associated with the big market. Thus, while revenue growth in the aggregate may confirm that the market is big, the revenue growth at firms collectively will fall below expectations and operating margins will be lower than expected because each of the individual firms overestimated its own prospects…There will be a period of reckoning, where some or many of the participants will recognize the gap between reality and expectations. When they do, the aggregate pricing of the sector will eventually decline with some of the entrants folding.

Grubhub provides a recent example of what this unwind looks like.

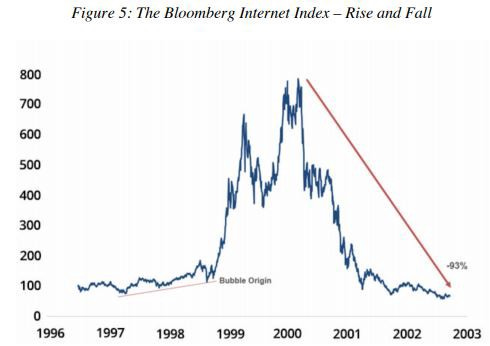

Returning to The Market is Huge!, other case studies range from e-commerce companies in the 1990s:

Source: Aswath Damodaran, The Big Market Delusion: Valuation and Investment Implications

To cannabis market in 2018:

Source: Aswath Damodaran, The Big Market Delusion: Valuation and Investment Implications

While the industries above vary, one common theme is that:

When asked to justify the pricing of a company in the market, especially young companies with little to show in terms of fundamentals, entrepreneurs, managers and investors almost always point to macro potential, i.e., that the retail or advertising or cannabis markets were huge. The interesting aspect is that they rarely express the need to go beyond that justification, by explaining why the specific company they were recommending was positioned to take advantage of that growth. In recent years, the big markets have gone from just words to numbers, as young companies point to big total accessible markets (TAM), when seeking higher pricing, often adopting nonsensical notions of what accessible means to get to large numbers.

Large markets are great, but at the end of the day TAM is not going to save you. You need more than a large market to build a growing, sustainable business. Business models matter. Some are good and some are bad. To be good you need to develop a moat, or competitive advantage. And you need to show up every day and work to widen that moat. And that’s just to stay in the same place.

Within companies, a large component of strategic planning is determining what projects deserve investment. Similar to entrepreneurs and investors, it’s easy to be seduced by new products, particularly when they serve large markets. While it doesn’t require twenty-one questions, one question that should be asked before creating a new product or entering a new market is “how can we do this better than our competitors?” If there’s no good answer, then a worthy follow up is “than why do it at all?”

👉 If you enjoyed reading this post, feel free to share it with friends!

For more like this once every weekend, consider subscribing 👇