Hi 👋 – Merry Christmas, happy holidays, and happy New Year. Today, the history of Spotify’s podcast strategy, one of the most popular posts from 2021. We’ll be back with fresh content on January 9, 2022. Thanks for reading. 🍾

“When a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact.” - Warren Buffett

Music streaming is a business with bad economics. The industry’s byzantine licensing structure has many mouths to feed1. For each dollar that Spotify earns streaming music, over $0.60 goes to artists, labels, and publishers. This doesn’t leave it much to build a reputation on.

Smart Pipes Become Dumb Pipes

Before the internet, buying music meant going to a store to buy a digital file on a plastic CD. Napster changed this by launching (illegal) peer-to-peer file sharing. Instead of buying whole albums, users could download single tracks. Unlike record stores, online shelf space is unlimited. People could access any song. Record stores became redundant. RIP, Tower Records. This is a classic case of the internet disintermediating the middleman. Distribution innovations, like the shift from physical CDs to digital downloads, enable new business models while hamstringing others2.

Spotify made Napster legal, charging users for speed and convenience. For a monthly fee, subscribers could access the world’s largest music library. But streaming music isn’t a durable advantage. Distribution innovations seldom are. Today, convenience and speed are table-stakes, not differentiators. Amazon Music, Apple Music, and YouTube offer similar services. What’s more, music is a commodity. Artists and labels want songs to be ubiquitous. Justin Bieber is particular about the provenance of his peaches, but isn’t picky about where his music is streamed.

Initially, Spotify grew by providing a better user experience around commoditized content. But similar to distribution innovations, product innovations can be short-lived. For example, Snapchat introduced stories in October 2013. Today, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and even LinkedIn have forked the feature:

Unless you have a structural cost advantage, relying on commoditized distribution and content isn’t a winning model. That’s Spotify’s predicament with music. The company differentiates with discovery, but like streaming technology, competitors are improving here. To differentiate, Spotify needed something unique and durable.

Follow the German Hackers

The benefit of being a platform is that people use your product in ways that you never anticipated. For example, in Germany, music labels owned the rights to audiobooks and music. Data analysts noticed that a few audiobooks were consistently among Germany’s top tracks. Additionally, German users who listened to both audiobooks and music had higher overall engagement versus music-only listeners. Adding audio increased listening time. This is how Spotify stumbled into podcasts.

Podcasts have two strategic benefits: supplying unique content and improving economics. Since 2019, Spotify has aggressively acquired studios like Gimlet, Parcast, and The Ringer and creator tools like Anchor, signed exclusive deals with Joe Rogan, Michelle Obama, and others, built out podcast ads infrastructure, and launched an in-house studio.

At the end of March 2021, the platform had 2.6 million podcast episodes available (not all are exclusive), 25% of users listened to podcasts3, and podcast streaming hours hit an all-time high. Podcasts improve user engagement and retention. Similar to the German finding, users who listen to both podcasts and music have higher overall listening time. Podcasts also encourage free users to convert to premium subscriptions, boosting LTV.

Management has repeatedly said that additional investments in podcasts are an indication that their strategy is working4. While podcasts have yet to transform the P&L, Spotify continues to invest. For example, on June 15th, the company inked a $60 million exclusive deal with Alex Cooper to bring her podcast Call Her Daddy to Spotify from Barstool Sports5. On June 17th, the company acquired Podz, which uses machine learning for podcast discovery6. Something is working below the surface.

The economic benefit comes from decoupling the direct relationship between streaming revenue and payouts to labels (cost of revenue). Relative to music streaming, which is variable, original and exclusive podcasts are fixed cost. After covering costs, incremental podcast revenue falls to the bottom line, improving profitability (here's more on that). That’s why, like Netflix, Spotify is investing heavily in exclusive and original content.

With podcasts, Spotify shifted from distribution innovation to content innovation. As Disney and Netflix proved, exclusive, high-quality content is bedrock for a solid business. If Spotify’s podcast bet pays off, it will have a content moat, providing differentiation and a more attractive P&L.

Connected Speakers & Patient Payoffs

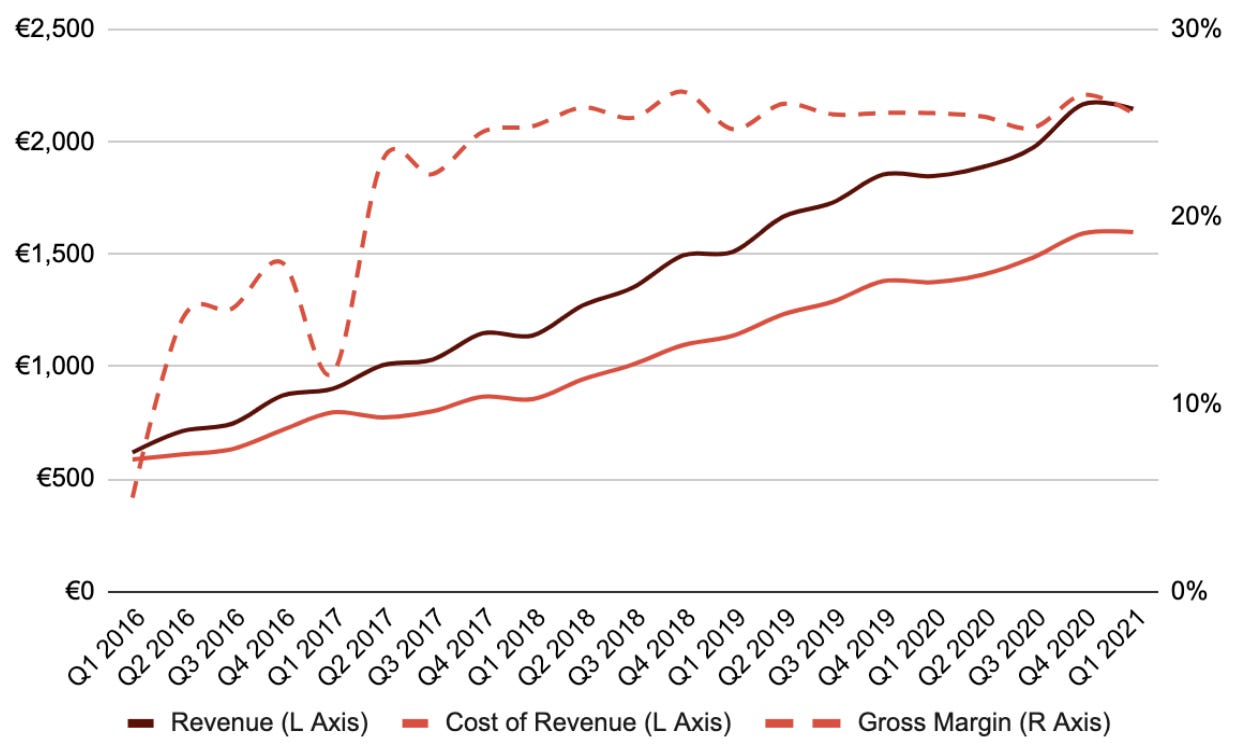

Good news about podcasts has shown up everywhere except for Spotify’s income statement. If the podcast strategy works, revenue and cost of revenue, which are currently moving in tandem, will diverge and gross margins will improve. On this scorecard, the strategy hasn’t paid-off. Yet.

Podcasts, and the broader push into audio (live audio, concerts, events), could transform Spotify’s P&L. History suggests this will take years. For example, in 2011, the company devoted significant engineering resources to building Spotify Connect, which lets users play music from the Spotify app to over 2,000 connected devices like cars, connected speakers, gaming consoles, and wearables. The upfront investment was large and the return didn’t come until seven years later when voice-activated speakers like Amazon Alexa and Google Home went mainstream.

Discussing Spotify’s connected speaker strategy, Sten Garmak, the company’s VP of Global Customer Experience said:

If you have an ambitious vision for a future, you need to allow it to take significant time to materialize. You need some strong conviction in the beginning, and then you need - you need enough management support and cultural support to be able to keep that investment alive for a long time. The things that turned out to be important for the long run also tended to be things that took quite a long time to move from inception to actual impact. But looking at it like in financial terms here and now, it's not the kind of investment that makes sense. But I think that's true for a lot of the things that we've done over the years. And a lot of things that our kinds of companies do - you know, there are compounding effects on beliefs, compounding effects on metrics.7

Compounding is an exercise in delayed gratification. It takes a while for the snowball to start rolling. At first it looks like nothing is happening. While many investors are focused on quarters, Spotify thinks in years. Their success needs to be measured in that timeframe as well.

Playing The Long Game

Daniel Ek, Spotify’s CEO, is playing the long game. His ambition is to win in audio - music, podcasts, live conversions - and grow the platform to one billion users. These are hairy, audacious goals that aren’t guaranteed to succeed. But Spotify has proven to be a flexible, savvy company able to go toe-to-toe against Apple and Google, despite structural disadvantages, like not controlling an app store and not coming installed by default.

When a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact. Spotify’s strategy acknowledges this. Good managers are able to change course and expand the TAM. Streaming music has poor economics, but Spotify’s audio strategy gives its management a chance to escape with its reputation intact.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers. ❤️

For more like this once a week, consider subscribing. ❤️

More Good Reads

Matthew Ball on the audio opportunity. Spotify’s eponymous Spotify: A Product Story provides a history of the company and its major product decisions. Episodes seven and nine on podcasting and becoming an audio platform were the basis for this note. Sleepwell Capital on Spotify and social audio. Below the Line on how Spotify can use product design to encourage podcast adoption.

Disclosure: The author owns shares in Apple and Netflix.

This framework comes from Matthew Ball who believes that media goes through three waves of competition: first access, then content, then platform. At some point, access becomes commoditized and media companies need to differentiate with content and platforms.

Spotify defines a user engaging with a podcast if they listened to one for greater than zero milliseconds. This is a weak definition. They could do better.

Per its 4Q 2019 shareholder letter.

TechCrunch, Spotify Acquired Podz, a Podcast Discovery Platform, June 17, 2021. More on the company’s technology:

Since podcasts are usually upward of 30 minutes long, it’s hard for listeners to browse new shows…So, Podz developed what it called “the first audio newsfeed,” presenting users with 60-second clips from various shows…Podz chooses a clip using its machine learning model, which was trained on more than 100,000 hours of audio in consultation with journalists and audio editors.

This comes from Hardware is Hard, episode six of Spotify: A Product Story. Here’s a link to the podcast and here’s a link to the show transcript.