#160 – Multiplying By Zero

The Capital Cycle, Convertible Bonds & More Layoffs at Wayfair

Hi 👋 – Charlie Munger’s first rule of compounding is to never interrupt it unnecessarily. Too much debt can short circuit the compounding process. That’s a useful framework for analyzing Wayfair, which last week announced its third major layoffs, despite market share gains and improving revenue growth. As always, thanks for reading.

🛋️ 🛋️ 🛋️ If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers.

🛋️ 🛋️ 🛋️For more like this, consider subscribing.

Staying Alive

You can’t grow if you’re dead. As such, survival is a precondition for success. Compounding – the eighth wonder of the world according to Einstein – is a function of rates and duration. While high growth rates ooze sex appeal and garner headlines, they’re frequently unsustainable. Over time, market and GDP growth exert their gravitational pull. Successful companies like Amphenol, Berkshire Hathaway, and Constellation Software grind out respectable growth decade after decade. Staying power is key.

Unhappy New Year

Over the past two years, tech companies have culled hundreds of thousands of employees. Wayfair has been particularly trigger happy, announcing three beefy restructurings since 2022:

August 2022: 870 employees laid off, representing 5% of Wayfair’s global workforce and 10% of corporate staff1.

January 2023: 1,750 employees laid off, representing 10% of Wayfair’s global workforce and 18% of corporate staff. The move was pitched as reducing management layers and improving agility2. About $1.4 billion in annual savings are expected, including the August 2022 cuts.

January 2024: 1,650 employees laid off, representing 13% of Wayfair’s global workforce and 19% of its corporate staff. The move is expected to yield cost savings of $280 million across salary, stock-based compensation (another form of salary), and capitalized technology labor (yet another form of salary)3. Similar to 2023, Wayfair thinned the ranks of senior- and middle-managers to flatten its org chart. After accounting for cost savings, Wayfair expects to generate $600 million of adjusted EBITDA in 2024, assuming no revenue growth.

Over this period, the company returned to growth, gained market share, and broke-even (on an adjusted EBITDA basis anyway). Typically layoffs of this magnitude are associated with companies heading in the other direction: slumping growth, bleeding market share, and mounting losses. What gives?

The Autopsy

Founded in 2002, Wayfair spent its first decade as a scrappy and frugal outfit. A lack of capital forced it to be lean, focused, and prioritize relentlessly4. This changed with an IPO in late 2014. Since then, the company has sporadically tapped the capital markets, taking advantage of easy capital.

As its coffers filled out, so did its management layers. Relentless prioritization gave way to less stringent green-lighting. The plenty supplanted the few. Some projects, like building out logistics infrastructure, were worthwhile. Many weren’t. As CEO Niraj Shah notes in his memo to employees surrounding the layoffs5:

Too many good ideas led to too few getting done.

Left unchecked, bureaucracy has the pernicious habit of feeding itself. Meetings beget meetings. Hiring begets hiring. Sand accumulates in the gears, slowing decision making and stymying progress (this is a major reason why Below the Line is such a fan of addition by subtraction).

Like many other tech executives, Shah admits to going overboard on hiring during a binge-fest of elevated demand and cheap capital6. When the tide reversed – as it always does – the downside of cheap capital fell into sharp relief.

Wayfair’s Balance Sheet

Indebtedness focuses the mind. Today, Wayfair is staring down the barrel of hefty upcoming debt maturities. Before the end of 2026, $1.8 billion is coming due. This compares to cash on hand of roughly $1.3 billion7 and a business operating just above breakeven. In other words, a bit of a hole. Though you won’t see it anywhere in their comms, this is the subtext of Wayfair’s recent layoffs.

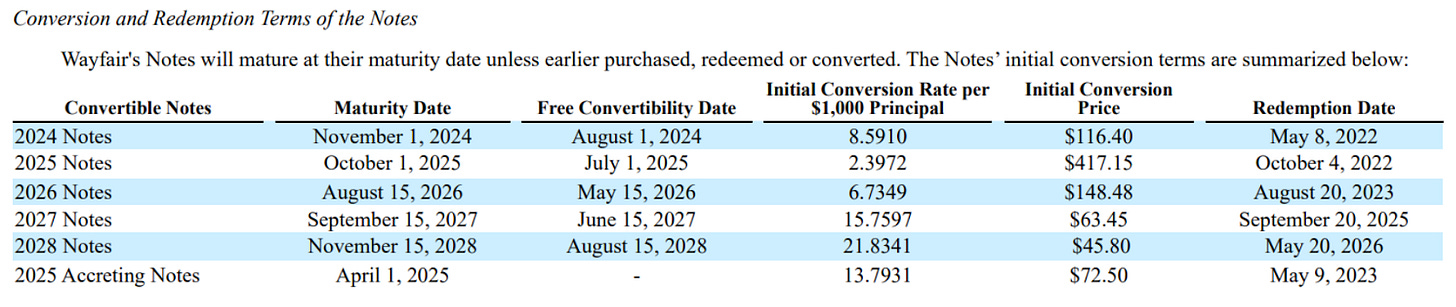

Convertible bonds account for the bulk of the outstanding debt. A convertible bond gives the holder the option to convert debt into a predetermined number of shares prior to maturity. They’re hybrid financial instruments that can take on characteristics of debt or equity depending on share price performance.

The benefits of convertible bonds include lower coupons than straight debt (because the option to convert to equity is valuable), raising capital with less dilution than a common equity issuance (because the conversion to equity happens at a 20% or more premium to prevailing market prices), and the ability to raise capital quickly (in as little as 24 hours).

Yet there’s no free lunch in finance. The downside of convertible bonds is that when things go south (or, stock prices aren’t rising), they turn into debt. While no one as ever confused me for a savvy financial engineer, this characteristic has always made me dubious about the value proposition of converts. Because debt can kill you (see: Farfetch), it’s the downside scenario that really matters. This is what Wayfair is wrestling with now.

The Capital Cycle

Wayfair is a case study in the ebbs and flows of the capital cycle. When capital is abundant, it’s easy for questionable projects to secure funding. When capital is scarce, only the best credits are funded.

Distressed credit investor Howard Marks provides a helpful distillation of the credit cycle in his November 2001 memo You Can’t Predict, You Can Prepare. To paraphrase Marks, during prosperous times, bad news is scarce, and providers of capital are flush. Risk aversion disappears and financial institutions compete to provide more capital. They do this by offering better rates (or, demanding lower returns), watering down credit standards, throwing covenants out the window, and writing bigger checks.

Now to quote Marks8:

At the extreme, providers of capital finance borrowers and projects that aren't worthy of being financed. As The Economist said earlier this year, "the worst loans are made at the best of times." This leads to capital destruction – that is, to investment of capital in projects where the cost of capital exceeds the return on capital, and eventually to cases where there is no return of capital.

At this point, the music stops. The tide goes out. People get caught swimming naked.

Back to paraphrasing, losses cause financial institutions to become gun shy. Risk aversion increases, interest rates rise, check sizes shrink, and covenants come back. Less capital is available. Some businesses go bust.

Eventually the pendulum swings in the other direction and the band starts to play again. So it goes. Marks’ main point is that cycles are inevitable and that investors need to understand where are in the cycle and act accordingly. (Be fearful when others are greedy.)

Wayfair’s converts are a relic from a period of easy capital. In a transaction that would make Howard Marks smile, the company priced $1.32 billion in convertible notes on August 12, 2020. They carried a conversion price of $417.15 and paid the microscopic coupon of 0.65%9. With the benefit of hindsight, Wayfair top-ticked the market.

The company’s stock is currently trading for around $55. In contrast, the conversion price on upcoming maturities range from $116 to $417. In other words, those converts most likely end up as debt, not as equity. And debt can kill you.

Wayfair has two options: repay or refinance. Assuming that you can do the latter is malfeasance, given you can never depend on the credit window being open when you need it. Even if Wayfair can refinance, the terms would be much worse given a substantial upward move in interest rates (goodbye, ZIRP) and a flaccid growth outlook (goodbye, Covid e-commerce boom). And so more cost cutting and layoffs.

Interestingly, the company noted that accounting for the latest cost savings, it expects to generate adjusted EBITDA of $600 million in 2024. Over the next three years, that equates to $1.8 billion in adjusted EBITDA, in-line with Wayfair’s debt maturities. That’s probably not a coincidence.

Getting Harder To Kill

Easy capital always leaves a few new gravestones in its wake. As Marks notes10:

The credit cycle contributed tremendously to the tech bubble. Money from venture capital funds caused far too many companies to be created, often with little in terms of business justification or profit prospects. Wild demand for IPOs caused their hot stocks to rise meteorically, enabling venture funds to report triple-digit returns and attract still more capital requiring speedy deployment. The generosity of the capital markets let companies sign on for huge capital projects that were only partially financed, secure in the knowledge that more financing would be available later, at higher p/e's and lower interest rates as the projects were further along. This ease caused far more capacity to be built than was needed, a lot of which is sitting idle. Much of the investment that went into it may never be recovered. Once again, easy money has led to capital destruction.

The contemporary analog to the dark fiber of the first dot-com bubble is excess headcount. As the cycle turns, the tech industry is correcting for its binge by moving away from the easy money paradigm to a more sober environment where profits and cash flows matter. Wayfair is no exception, as CEO Niraj Shah notes11:

While the investment community will focus on the cost savings numbers today, the key thing for us to focus on is that a company cannot win over time unless it gets more done per dollar spent than its competitors.

Getting more done per dollar than your competitors is a wise objective. While debt can kill you, frugality makes you harder to kill.

Rule number one: avoid multiplying by zero.

🛋️ 🛋️ 🛋️ If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers.

🛋️ 🛋️ 🛋️For more like this, consider subscribing.

More Good Reads and Listens

Wayfair CEO Niraj Shah’s mea culpa to employees regarding the January layoffs. While most of these memos are sanitized and filled with platitudes, this one is worth reading as it provides context behind Wayfair’s decision making. His point on the insatiable appetite of stakeholder management is a good one. You Can’t Predict, You Can Prepare by Howard Marks. If you’d prefer to listen (Here’s an audio version). Below the Line on Wayfair’s Lost Decade and Minsky Moments.

Disclosure: The author owns shares in Berkshire Hathaway.

The New York Times, Wayfair will lay off 870 workers after a drop in sales, August 19, 2022.

Wayfair, Wayfair Announces Update to Cost Efficiency Plan and Business Performance, January 20, 2023.

Wayfair, Wayfair Announced Workforce Realignment Plan, January 19, 2024.

Wayfair, A Message From Wayfair CEO and Co-Founder Niraj Shah, January 19, 2024.

Wayfair, A Message From Wayfair CEO and Co-Founder Niraj Shah, January 19, 2024.

Wayfair, A Message From Wayfair CEO and Co-Founder Niraj Shah, January 19, 2024.

Wayfair, 2023 Q3 Form 10-Q, October 25, 2023.

Howard Marks Memo, You Can’t Predict. You Can Prepare, November 2001.

Wayfair, Wayfair Inc. Prices Offering of $1.32 Billion Convertible Senior Notes, August 12, 2020.

Howard Marks Memo, You Can’t Predict. You Can Prepare, November 2001.

Wayfair, A Message From Wayfair CEO and Co-Founder Niraj Shah, January 19, 2024

Well said Kevin.

While Niraj has been direct about taking responsibility for the operational mistakes, little (or nothing) has been said about Wayfair's atrocious capital allocation over the last few years.

Not only did the company waste precious capital on buying back stock at inflated values, but some of the cheap capital raised thru the converts has been pissed away on buying calls to minimize potential dilution from the converts.

from the 10K: "Wayfair used approximately $93 million, $255 million, $146 million and $80 million of the net proceeds from the 2024 Notes, 2025 Notes, 2026 Notes and 2027 Notes, to purchase

the Capped Calls."

Great work Kevin, thank you!