Hi 👋 - Bill Gurley is a general partner at Benchmark with deep expertise in online marketplaces. His blog, Above the Crowd, chronicles the rise and fall and rise again of tech over the past two decades. It’s a great resource for learning about online business models. This week, a look at the uses and abuses of the lifetime value formula, a frequent topic for Gurley. Next week, a look at Gurley’s most important metric. Thanks for reading.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers.

For more like this once a week, consider subscribing.

LTV 101

The value of a business is the present value of its customers’ future cash flows. Businesses grow by acquiring new customers, retaining existing customers, and improving monetization (getting customers to pay more). The consumer lifetime value (LTV) framework attempts to make sense of all this. LTV outputs how much a company can spend acquiring a customer, given its attributes. A customer that spends a lot of money and sticks around for decades justifies a high acquisition cost. A customer that makes one small purchase and then churns doesn’t.

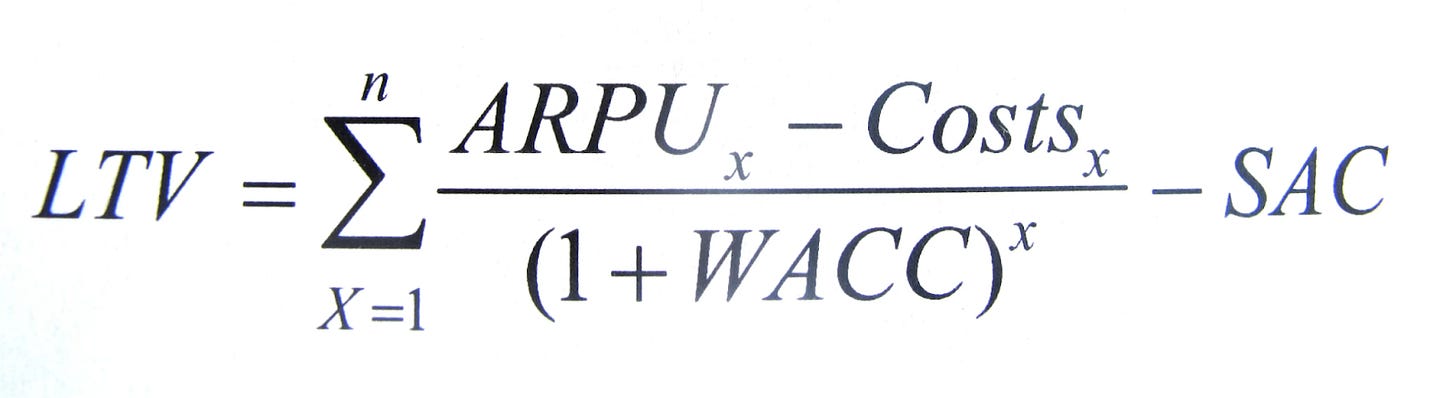

The formula looks like this:

The variables driving the LTV model are:

Average Revenue per User (ARPU): The revenue a customer generates per year. More frequent purchases and higher order values increase ARPU. All else equal, higher is better.

Average Customer Lifetime (n): How long do customers stick around for? The longer, the better. This is the inverse of churn1.

Costs: How much does it cost per year to support a customer? Customer support and retention marketing should be incorporated here. Lower is better.

Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC): A dollar in the future is worth less than a dollar today, so WACC is used to discount future revenue. WACC incorporates the time value of money into LTV.

Subscriber Acquisition Costs (SAC): The cost to acquire a customer. This is synonymous with customer acquisition cost (CAC). Lower is better.

That’s the theory. Reality is a lot messier.

Garbage In, Garbage Out

All models are wrong, but some models are useful. Gurley argues that LTV models are easy to misuse or abuse. For starters, it represent a simplified view of the world, not reality. Forgetting this is dangerous.

While the LTV formula seems scientific - there’s a sigma after all - business is not physics. Aside from “don’t run out of cash,” there are few absolute business laws. With the LTV model, it’s easy to conflate precision with accuracy. You can dial your assumptions to three decimal places, but that won’t necessarily make them more accurate. The risk of the LTV model, or any model for that matter, is that you think you’re operating in the lower right quadrant (below), when in fact you’re in the top right. As physicist Richard Feynman said:

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself — and you are the easiest person to fool.

Models are only as good as their underlying assumptions. Garbage in, garbage out. Relax an assumption and the LTV model will suggest spending more on marketing. Increase your customer lifetime assumption - and voila - you can pay more to acquire a customer. Whether that customer sticks around for longer is another matter. Layer on the natural tendency for managers to want to grow their budgets, and you’ve got pressure for more lenient assumptions. That’s why Gurley advocates that finance and not marketing run the LTV model.

What’s more, the LTV variables are interdependent. Gurley likens them to five horsemen attached by ropes, all headed in different directions. When a horse pulls in one direction, it's difficult for the other four to go where they want to go. For example, lowering price reduces churn, but it also decreases ARPU. Similarly, enhancing customer support and retention marketing improves longevity, but it also increases costs. All decisions involve trade-offs. There's no free lunch. It's unlikely that all metrics will go up-and-to-the-right.

Additionally, LTV variables change over time. Unless you're blessed with network effects - and few businesses are - customer acquisition likely gets harder over time. There's more competition for keywords on Google and lookalike audiences on Facebook. Each marketing channel can only support so much efficient spend. There’s a tension between scaling budgets and spending more efficiently. Gurley sees performance marketing as a grind that gets harder over time.

Taking a Measuring Tape to a Knife Fight

A PowerPoint isn’t a strategy. Neither is a model. Sustained growth and profitability requires differentiation and competitive advantage. Gurley argues that putting too much weight on the LTV model blinds companies to this distinction. Increasing marketing can drive growth for a while, but running the same playbook as everyone else won’t deliver superior results. As Gurley says2:

Some people wield the LTV model as if they were Yoda with a light saber; “Look at this amazing weapon I know how to use!” Unfortunately, it is not that amazing, it’s not that unique to understand, and it is not a weapon, it’s a tool. Companies need a sustainable competitive advantage that is independent of their variable marketing campaigns. You can’t win a fight with a measuring tape.

A heavy focus on LTV also creates blindspots. For example, organic customers are usually a company’s best customers. Some of the most viral products and marketing campaigns have come from start-ups without large marketing budgets. LTV logic misses this. Gurley likes to ask if a business is buying their customers or renting them. Money spent on marketing could also be spent on building a better product, improving the consumer experience, or lowering prices. This is one of the reasons why Jeff Bezos pulled back on Amazon's TV marketing in favor of cutting prices. Give a customer a good product at a good price, and you'll generate word-of-mouth marketing. Bezos’ philosophy was:

More and more money will go into making a great customer experience, and less will go into shouting about the service. Word of mouth is becoming more powerful. If you offer a great service, people find out3.

Lastly, LTV relaxes the need for near-term profitability. CAC goes out the door today and the payback comes at some point in the future. But some days never come. The future is uncertain and the competitive landscape in tech changes quickly. Today's assumptions may not be tomorrow's reality.

LTV should be viewed as a tool to evaluate alternative marketing programs, not as gospel.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers.

For more like this once a week, consider subscribing.

More Good Reads

Gurley’s blog, Above the Crowd, is a great resource for understanding online businesses. The Dangerous Seduction of the Lifetime Value Formula is referenced frequently in this note and is a post I re-read at least once per year. The Ben Thompson Starter Kit from Below the Line.

Churn = 1 / customer lifetime or 1/n. If a customer lifetime is five years, you’d expect 20% of customers (⅕) to churn every year.

Bill Gurley, Above the Crows, The Dangerous Seduction of the Lifetime Value (LTV) Formula, September 4, 2012.

As quoted in The Dangerous Seduction of the Lifetime Value (LTV) Formula by Bill Gruley.