#72 - The Joy of Forced Experimentation

Transit Strikes and A/B Testing

Hi 👋 - Inertia is a powerful force. Without much thought, it’s easy to slip into a routine. Disruptions like a transit strike (or a pandemic) can shake up routines and drive lasting behavior change. Constantly testing and experimentation isn’t a default behavior for individuals or businesses, but it is beneficial. Thanks for reading!

Many new readers discover Below the Line when a friend or coworker shares it with them 🚇

Not a subscriber yet? You can fix that here:

In February 2014, portions of the London Underground shut down for three days as employees went on strike over plans to close ticket offices and eliminate 1,000 jobs1. For commuters, the shutdown caused widespread misery. For economists, it sparked joy.

A Striking Finding

The partial Tube shutdown created a natural experiment, making economists giddy. With certain stations and train lines shuttered, some commuters were forced to find a new way into the office while others weren’t affected.

Economists Shaun Larcom, Ferdinand Rauch and Tim Willems analyzed individual’s travel data on the London Underground from January 19, 2014 to February 15, 2014 to suss out the impact of the transit strike2. Their findings are, well, striking.

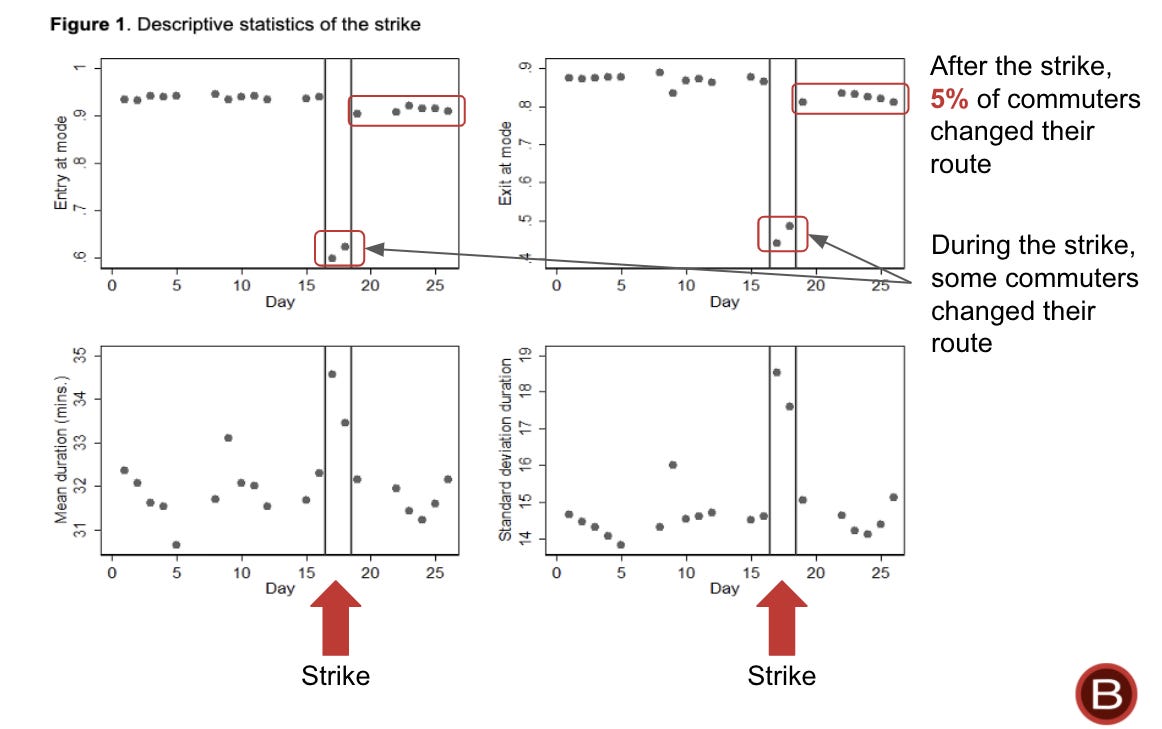

Before the strike, about 90% of riders got on and off the Tube at the same stations every day3. The transit strike, demarcated by the vertical lines in the figure below, forced behavior change as some stations closed. During this time, roughly 30% of commuters altered their entry point. A similar percentage changed their exit point.

Larcom, Rauch and Willems found that:

The strike brought about some lasting changes in behavior, as the fraction of commuters that made use of their modal station seemingly drops after the strike.

Ultimately, 5% of commuters stuck with their new route after the strike, implying that they found a better alternative during the disruption. You can see this on the top two charts above: the dots after the strike are slightly lower than the dots before the strike, indicating some new commutes.

Long Inertia

These better alternatives weren’t new. They had been available to commuters before the strike. The economists offer two potential explanations for this (gasp) seemingly irrational behavior. The first is that consumers are rational and that search costs - opening Google Maps, trial-and-error with new routes - caused them to give up before finding the optimal alternative. The second is that commuters were never maximizing or optimizing, but instead looking for a good enough solution, a behavior that Nobel Prize winning economist Herb Simon dubbed satisficing. Some mornings, just making it to the subway in one piece sans optimization feels like a win, so I’m partial to the second explanation. Additionally, psychology and behavioral economics have repeatedly shown that calculating rationality is more the purview of economic textbooks than real life.

Despite three days of headaches, Larcom, Rauch and Willems conclude that the strike produced a net benefit: 5% of commuters had a better way into work. The disruption imposed constraints forcing experimentation that wouldn’t have happened otherwise. Stepping back, the trio concludes that we should shake it up more often:

If we behave anything like the satisficing commuters on the London Underground network and experiment too little, hitting such constraints may very well be to our long-run advantage. Encouraging ourselves to implement occasional routine-breaks could be beneficial as well.

Up Schitt’s Creek

If the three day partial transit strike in London were a rainstorm, then the ongoing Covid pandemic is a hurricane mixed with an earthquake, volcanic eruption, landslide, plague of locust, sinkhole and shark attack4. The short-lived transit disruptions caused lasting behavioral change in London, so there’s no doubt that the global struggle with Covid will also lead to large behavioral changes.

Covid forced people to experiment with a kitchen sink of new behaviors: mask wearing, ordering groceries online, home workouts, baking sourdough bread, watching Schitt’s Creek and writing on Substack to name a few5. Some will stick. Some won’t.

Rough contours of the post-Covid world are emerging. For example, after a successful forced experiment with working-from-home, JP Morgan said it only needs 60 seats per 100 employees looking forward, significantly reducing its real estate needs6. Many companies will follow suit. Moving back underground, Covid has decimated public transit ridership globally. In Shanghai, which is largely open and virus-free, public transit ridership is 10% below pre-pandemic levels7. Expect post-Covid normal to be different from pre-Covid normal.

Experimental Cultures

Experimentation, whether voluntary or forced, benefits companies as well as individuals. A benefit of technology businesses is the ability to A/B test on a massive scale. A/B tests are randomized online experiments measuring two approaches, A and B, to see which produces better results. Examples of variables that can be A/B tested are the flow of a conversion funnel, homepage layout, or the size or color of an add-to-cart button.

Online travel site Booking.com has a reputation for savvy experimentation. One of its tenets is that anyone in the company can test anything without management's permission. According to Harvard Business Review8:

Booking.com runs more than 1,000 rigorous tests simultaneously and, by my estimates, more than 25,000 tests a year. At any given time, quadrillions (millions of billions) of landing-page permutations are live, meaning two customers in the same location are unlikely to see the same version. All this experimentation has helped transform the company from a small Dutch start-up to the world’s largest online accommodation platform in less than two decades.

Only 10% of Booking.com’s tests succeed, so businesses need to tolerate failure and view it as a step on the path towards success. For some managers and organizations, this is a tough pill to swallow.

Massive user bases and datasets create giant petri dishes for tech firms. This is one advantage that bits businesses have over atoms businesses. With user bases in the tens or hundreds of millions, a basis point or two of improvement here and there produces a meaningful uplift. Over time, the aggregation of marginal gains snowballs, like compound interest. I saw this firsthand while at Etsy in late 2017 when increasing testing velocity became a priority. Every test didn’t succeed, but all provided data and insights, helping generate new hypotheses. Ultimately, increased testing velocity helped reaccelerate GMV growth.

Experimentation can spark joy for individuals and companies. Economists shouldn’t be the only ones having fun.

Keep experimenting, subscribe! 🔬

Test out Below the Line on friends and coworkers 🧪

More Good Reads

Harvard Business Review on the primitives needed to build a culture of experimentation. In a competitive market, you need to run fast and experiment a lot just to stand still. Below the Line on The Red Queen Effect and Google’s competition with online travel agencies like Booking.com and Expedia.

The Guardian, London tube strike causes travel delays throughout capital, February 5, 2014.

Shaun Larcom, Ferdinand Rauch, and Tim Willems, The benefits of forced experimentation: Striking evidence from the London underground network, September 15, 2015.

Each dot on the chart represents the commutes modal station, which Larcom, Rauch and Willems define as the station commuters used most frequently before the strike.

This is probably an understatement.

While this list is lighthearted, it’s not intended to diminish the physical, emotional, mental, and economic burdens of Covid which are equally staggering and horrifying. I’ve been fortunate to be able to do my job from home over the past year. Globally, billions aren’t so fortunate. Covid sucks.

From JP Morgan’s 2020 Annual Letter:

Remote work will change how we manage our real estate. We will quickly move to a more “open seating” arrangement, in which digital tools will help manage seating arrangements, as well as needed amenities, such as conference room space. As a result, for every 100 employees, we may need seats for only 60 on average. This will significantly reduce our need for real estate.

If you don’t want to read all 66 pages, here’s a summary of the letter.

New York Times, Riders Are Abandoning Buses and Trains. That’s a Problem for Climate Change, March 25, 2021.

Stefan Thomnke, Harvard Business Review, Building a Culture of Experimentation, March-April 2020 Magazine.