Hi 👋 - At scale, marketplaces are wonderful businesses. But getting them to scale is fiendishly hard. That’s because of the chicken-and-egg problem with supply and demand. This note takes a look at marketplace liquidity. Thanks for reading.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends. ❤️

If you’re not a subscriber yet, you can subscribe here 👇

Big is Beautiful

Marketplaces sell transactions. They connect supply and demand, facilitating commerce. For example, Uber connects drivers (supply) and riders (demand), taking a cut of the revenue for playing matchmaker. Similarly, Airbnb connects hosts (supply) with guests (demand), and also takes a cut.

At scale, marketplaces are beautiful businesses. First, they’re asset-light. They don’t need to buy inventory or require heavy capital expenditures. While American Airlines needs to buy Boeing 747s, Uber doesn’t need to purchase a fleet of vehicles, it just needs to acquire drivers. Additionally, marketplaces have network effects. Buyers want to be where sellers are and sellers want to be where buyers are. More sellers attract more buyers and vice versa. This sparks a virtuous cycle and is why marketplaces tend to be winner-takes-most. Asset-light plus network effects equals potentially fat profits. However, scale is the operative word. Scaling a marketplace is hellishly difficult.

What is Marketplace Liquidity?

What makes marketplaces difficult to crack is the chicken-and-egg problem. How can you create demand when there’s no supply? How can you create supply when there’s no demand? Welcome to the existential dilemma of a marketplace entrepreneur.

Let’s say you open Uber and the next available driver is 47 minutes away. If this happens a few times, you’ll probably uninstall the app. That’s the risk of limited supply. Similarly, an Uber driver that’s not getting fares isn’t making any money. He’s unlikely to stick around. That’s the risk of limited demand.

To succeed, marketplaces must balance supply and demand. Marketplace liquidity measures how efficiently buyers and sellers are matched. It’s the likelihood of finding what you’re looking for. If you want falafel delivered, can you get it? The ability of a marketplace to create matches is governed by the quantity and quality of sellers and buyers.

Here’s a useful framework for marketplace from Julie Morrongielle, an investor at Point Nine Capital1:

Buyer Liquidity: The likelihood that a search leads to a transaction. For example what percentage of Lyft requests result in a ride? If you’re looking for Sichuan food on DoorDash, can you find it? The metric to track here is search to fill rate.

Seller Liquidity: A measure of supply usage. For example, what percentage of rooms on Airbnb are booked on a given night? Utilization rate is the key metric.

Buyer to Supplier Ratio: How many buyers can a one supplier serve? An Etsy seller can transact with multiple buyers. In contrast, an Uber driver could only service once fare at a time. Viewed through this lens, Uber Pool - multiple riders with the same driver - is a tactic for Uber to increase seller liquidity and improve its buyer to supplier ratio, without increasing the number of drivers. This metric is most relevant where there’s a one-to-one relationship between buyers and suppliers.

More Addition by Subtraction

To achieve marketplace liquidity, entrepreneurs must focus. In his series on scaling marketplaces, Lenny Rachitsky, a former PM at Airbnb and current author of Lenny’s Newsletter, interviewed operators from seventeen marketplaces including Airbnb, Etsy, Instacart, and Uber. Sixteen of the seventeen initially constrained their marketplace to get critical mass2. Similarly, in Liquidity Hacking, early oDesk employee and current VC Josh Breinlinger writes that3:

It often requires narrowing the scope drastically of the offering until sufficient scale allows you to expand to achieve a broader marketplace...In almost all cases, it helps to really focus the efforts of the business. You have very limited resources to get to a sustainable marketplace so you should concentrate your resources on small areas.

Yet again, addition by subtraction.

Most marketplace founders start by focusing on a particular geography or product category. For example, DoorDash constrained geographically, focusing on food delivery in Palo Alto and suburban Silicon Valley, while Etsy constrained on category, focusing on vintage and handmade.

In Rachitsky’s research, the only company that didn’t constrain was Thumbtack, a marketplace for local services like contractors, electricians, and home cleaners. Thumbtack did this because its transactions were low frequency and high value. Unlike ride sharing or food delivery, which are high frequency, people remodel their house or need plumbing work sporadically. As such, Thumbtack had to cast a wide net to build a business.

Liquidity Hacking: Supply

Most marketplaces attack the chicken-and-egg problem by tacking supply first. Fourteen of the seventeen marketplaces Rachitsky surveyed did this. One reason why is that supply can drive demand. For example, once acquired, restaurants helped market Caviar, DoorDash, and GrubHub (think: window stickers).

Building supply is hand-to-hand combat. It’s going door-to-door, scanning paper menus then uploading them online, founders delivering food, and a whole host of other things. Scaling marketplaces is a grind.

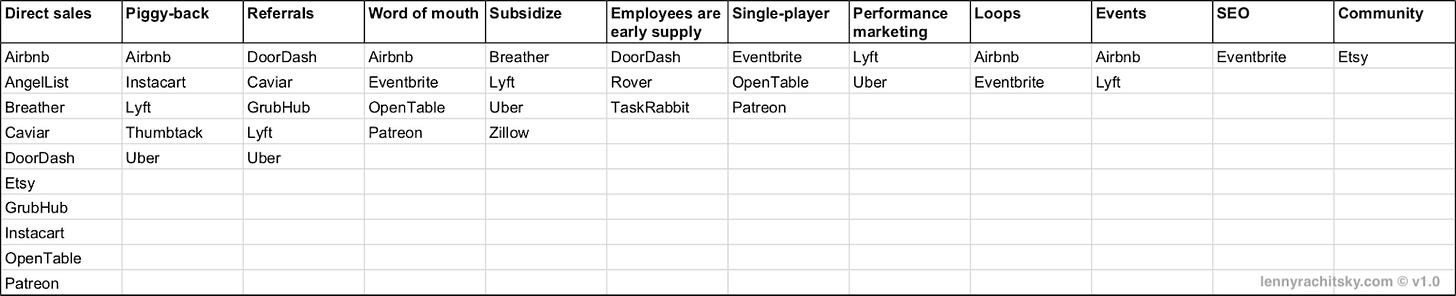

Rachitsky identified twelve supply growth levers, but for each marketplace most of the benefits came from just two or three4. The most common were:

Direct Sales: Classic ground and pound. DoorDash, GrubHub, and OpenTable employees went restaurant to restaurant, pitching owners. Etsy employees scoured in-person craft fairs, talking up sellers.

Piggy-Backing: Leveraging information in existing networks, namely Craigslist. Scraping and aggregating existing information and presenting it in a new way. Zillow did this.

Referrals: Incentivizing your existing supply to bring on new supply. This tactic was successful for Uber and Lyft.

Less frequently used tactics included subsidies, using employees as suppliers, and offering a product with stand-alone value to one side of the marketplace. For example, Uber guaranteed hourly rates and Lyft set income floors for drivers. In the early days of DoorDash, the company was short on drivers and Tony Xu, co-founder and CEO, frequently made deliveries. Even today, DoorDash employees deliver meals occasionally.

At my company, job search website Indeed, a key lever of our early supply growth was creating a platform for businesses to post a job for free. If you’re Google or Goldman Sachs, you don’t have any trouble driving traffic to your careers page. In fact, you’re likely drowning in applications. However, if you’re a plumber in Akron, Ohio or an auto body repair shop in Paris, Texas you probably don’t have a career site (perhaps you don’t even have a website) and if you do, driving traffic there would be difficult. Indeed provided a free recruiting platform. This is an example of providing a tool with stand-alone value to suppliers (what Rachitsky calls single-player mode). Individually, none of these jobs would attract much demand, but when you start aggregating millions of posting, it attracts job seekers. Even better, some of this supply was unique: because it was hosted on Indeed, you could only find it there.

Liquidity Hacking: Demand

Most marketplaces focus on demand once product/market fit is established and supply is coming easy(ish) or supply is heavily utilized5. Common demand levers were:

Word of Mouth (WOM): This was used by half marketplaces. For example, Lyft's pink mustaches sparked conversation, helping word of Lyft spread. Over 50% of Airbnb’s guests and hosts found the platform through WOM.

Supply Generated Demand: Some supply brings its own demand with it. For example, restaurants helped market DoorDash and GrubHub. In marketing their events, organizers using Eventbrite brought demand onto the platform.

Search Engine Optimization (SEO): SEO is an effort to make your site show up near the top of Google’s SERP. SEO represents a potentially huge, free traffic source. About 40% of marketplaces used this tactic.

Other demand driving tactics include performance marketing, PR, and loops. For example, during the 2008 financial crisis journalists wanted data on home prices. Zillow made this information readable accessible, driving lots of press coverage. Some craft sellers on Etsy bought their supplies from other Etsy sellers, creating a loop.

Why Liquidity Matters

Marketplace liquidity is crucial, because it drives network effects. It’s what greases the flywheel. It’s also a prerequisite for generating juicy profit margins. One of Rachitsky’s findings for a given marketplace, supply and demand levers are often different. Similarly, none of these strategies are a silver bullet.

While the tactics above worked for the current generation of marketplaces, the next generation may require a new playbook. What won’t change is the how hard it is to scale a marketplace.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends. ❤️

If you’re not a subscriber yet, you can subscribe here 👇

More Good Reads

This note leans heavily on Lenny Rachitsky’s excellent work. If you’re interested in marketplaces and hearing directly from the people who built them, this is a great place to start: cracking the chicken-and-egg problem, supply vs. demand, growing supply, and growing demand.

Julia Morrongiello, WTF is Marketplace Liquidity?, October 4, 2019.

Lenny Rachitsky, Lenny’s Newsletter, How to Kickstart and Scale a Marketplace Business – Phase 1: Crack the Chicken-and-Egg Problem, November 20, 2019.

Josh Breinlinger, Liquidity hacking: How to build a two-sided marketplace, November 20, 2012.

Lenny Rachitsky, Lenny’s Newsletter, How to Kickstart and Scale a Marketplace Business – Part 3: Cracking the Chicken-and-Egg Problem 🐣 - Growing Initial Supply, November 22, 2019.

Lenny Rachitsky, Lenny’s Newsletter, How to Kickstart and Scale a Marketplace Business – Part 4: Cracking the Chicken-and-Egg Problem 🐣 - Growing Initial Demand , November 22, 2019.