Hi 👋 - I’m doing some traveling the next two weeks, so dipping into the archives for a look at eBay. E-commerce seems inevitable in retrospect, but its initial prospects were fraught. According to the Pew Research Center, in 1995 only 8% of Americans were comfortable buying something online with a credit card. eBay is the great grandmother of US e-commerce, creating a market and blazing a trail for companies that would come after like Airbnb, Booking.com, and Etsy. This week begins a deep dive into eBay, based on Adam Cohen’s book, The Perfect Store: Inside eBay. Thanks for reading.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers. 🛍

For more like this once a week, consider subscribing. 🛍

The Perfect Market

Before the internet, the perfect market was an economics textbook pipe dream. A perfect market would have plenty of buyers and sellers. It would also have minimal search and transaction costs. Even in large cities, with high retail density and diversity, this ideal was a ways off. Transactions required rummaging through bins at a record store or driving somewhere only to find out that the item you were looking for was out of stock.

In 1995, eBay founder Pierre Omidyar, equal parts hippie, libertarian, and philosopher, realized that the internet allowed perfect markets to exist in real life. It could power a global marketplace connecting sellers with the buyer willing to pay the most for a specific good, be it JFK’s autograph or a vintage PEZ dispenser.

The internet aggregates geographically dispersed buyers and sellers and removes physical proximity as a prerequisite for commerce. Whether you were in London, Lagos, Little Rock, if you had a credit card and a reliable internet connection, you could participate. It also made it easier for individuals to carry out transactions that would formerly require intermediaries.

Many users and employees, including former CEO Meg Whitman, were initially unimpressed when they first saw eBay’s website. The UX and functionality were inherently threadbare. The site consisted of a search bar, listings, message boards, and feedback forum. But the magic of eBay wasn’t its look and feel, it was the mass of buyers, sellers, and listings, which, like a magnet, attracted more.

eBay faced competition from start-ups like Auction Universe to (former) tech giants like Yahoo, but none could match its liquidity. Buyers want sellers, sellers want buyers, and eBay had both in spades. According to Cohen:

The other reason eBay's first-mover advantage was so real was that its rise was a product, as Omidyar and Skoll liked to say, of a “virtuous cycle.” Buyers came to eBay because it was where all the sellers were; sellers came because it was where all the buyers were. Once eBay achieved critical mass, which it did early on, it would have made no sense for users to go to any other site.

Ghanaian Black Stars and Swedish Chrome Fluters

There’s a lot to love about living in New York City. One thing that always gets me is that during the World Cup, there’s a bar repping every national team. Costa Rica, Senegal, Uruguay, you name it. Most places aren’t like New York. If you’re a fan of Ghana's national team, the Black Stars, but you live in Council Bluffs, Iowa, you might have to watch the game alone.

There are almost eight billion people on the earth, each with heterogeneous tastes and preferences. This creates never ending niches. However, unless you live in a city with high population density, there’s a good chance that you might be the only person in your zip code with a taste for collecting antique typewriters or growing carnivorous plants. To an extent, the internet removes the constraint of geography. While a Black Stars fan in Council Bluffs might struggle to find another fan to raise a pint with, there are plenty of Black Star fans online. This is eBay’s core insight. The ability to connect geographically dispersed buyers and sellers was one of the greatest strengths of the internet and one that eBay leveraged to great effect. Buyers and sellers who were thousands of miles away physically, were only a few clicks away online.

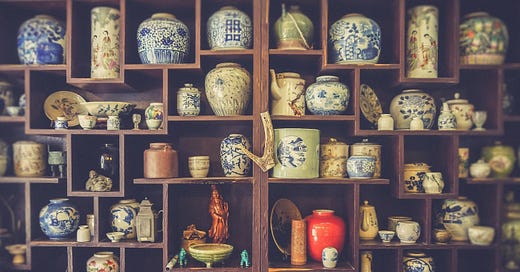

eBay started with a handful of categories: automotive, antiques and collectibles, books and comics, computer hardware and software, consumer electronics, and miscellaneous. By 1997, antiques and collectables dominated, accounting for almost 80% of listings. That’s because the company improved the shopping experience and its message boards created a place to meet up and hang out.

Many collectors are geographically isolated. If you were passionate about vintage duck decoys or southwestern folk art, you might have to travel across state lines to attend a craft fair or conference with like minded individuals. Connecting far-flung buyers and sellers online was more efficient than the flea markets and trade fairs that collectors had historically relied on1.

For buyers, eBay reduced the time, effort, and expense required to find what they were looking for. Items that a buyer could spend weeks, months, or years searching for offline - say vintage buttons, or a rare pickle jar from the 1840s - were available 24/7 from the comfort of their home.

For sellers, eBay improved traffic and sales velocity. Before the internet, if you ran an antiques store in Hudson, New York, your market was limited to whoever walked into your store. With eBay, your market was global, expanding the pool of buyers (and also of competition). If no one in Hudson wanted your goods, perhaps someone in Helsinki or Hong Kong would.

This process created different winners and losers, as Cohen recounts in a story about an antiques dealer and Swedish fluters from the 1950s. A fluter is a specialized kind of sad iron used to press fluted ruffles on linen cuffs and collars2:

In the late 1990s, Swedish chrome fluters from the 1950s became popular in the US sad iron collecting community. There was plenty of inventory in Sweden, but no one in Sweden knew that Americans would pay hundreds of dollars for it. At first, American dealers were able to buy the fluters in Europe, and then sell them in the US at huge markups. Eventually, Swedish fluter supply made its way on to eBay. As supply increased, prices predictably dropped. What dealers could once sell for $500 later sold for about $100.

This was Omidyar’s dream in action: creating a more efficient market by connecting buyers and sellers globally. Collectors in America were happy to add to their collections and sellers in Sweden were pleased that something collecting dust turned out to have value. However, for the dealers who once earned fat margins selling fluters, this was a nightmare as they were being disintermediated.

Auction Theory

Returning to the economics textbook, another characteristic of perfect markets is that goods go to the buyer with the highest willingness to pay. Theoretically, auctions maximize value for sellers and buyers3. That’s why Omidyar built eBay as an auction platform.

Because they’re labor intensive and time consuming, auctions are not a great way to sell most goods. Where auctions excel is for goods where the value is indeterminate, which is another reason why antiques and collectables did so well on eBay. Unlike a Twinkie or roll of toilet paper, where value is reasonably well understood, categories like antiques and collectables are influenced by factors like scarcity and sentimental value, resulting in a wide range of valuations. One man’s trash is another man’s treasure.

For a marketplace or an auction to work, it needs to have a lot of potential bidders. From the start, eBay maintained a leading position with buyers, sellers, and listings, becoming a clearinghouse for all sorts of goods. As Cohen writes:

With millions of buyers and sellers able to participate in every transaction, market flaws that allowed goods to sell for more or less than they should have were being corrected. eBay was now a price-setting mechanism—a stock market for everyday goods.

While eBay moved commerce in the direction of a perfect market, perfection is an impossible ideal. Auctions on eBay had fixed durations, either three, five, or seven days. When the clock hit zero, the auction was over, even if there were eager bidders with a higher willingness to pay. In contrast, a traditional auction will continue until all bidding is exhausted. This is a quirk of eBay’s initial design and the fact that Omidyar created the website as a nights and weekends project, not thinking it would eventually become a public company.

To be continued. That’s all for this week. Next week we’ll pick up with eBay’s business model, the Million Auction March, and more. Thanks again for reading.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers. 🛍

For more like this once a week, consider subscribing. 🛍

More Good Reads

This note is based on Adam Cohen’s book, The Perfect Store: Inside eBay. If you’re interested in my book notes, give me a shout. Happy to share a Google doc with you. Bill Gurley on the factors that determine success for online marketplaces. Below the Line on take rates and how marketplaces make money.

Disclosure: This post contains an Amazon affiliate link to Adam Cohen’s book, from time to time we’ll discuss a book and include an Amazon affiliate link. If you’re interested in the book and purchase through the link, Jeff Bezos throws a few pennies in my direction.

Efficiency in this case is defined in an economic sense: it’s easier for buyers and sellers to meet and transact and the buyer with the highest willingness to pay wins the auction. There are social and other aspects that some collectors missed, for example, the thrill of the hunt.

McLeod County Historical Society, Object Record: Two-piece Geneva hand fluter.

Wikipedia contributors, "Auction theory," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia,https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Auction_theory&oldid=1037614643 (accessed August 20, 2021).