Hi 👋 - Today, part two of a deep dive into eBay, based on Adam Cohen’s book, The Perfect Store: Inside eBay. If you’re new to Below the Line this week, here’s part one. Thanks for reading.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers. ❤️

It’s Just Too Weird

eBay was the rarest type of startup: profitable. Helped by its asset light model, the company made money from its first month onward.

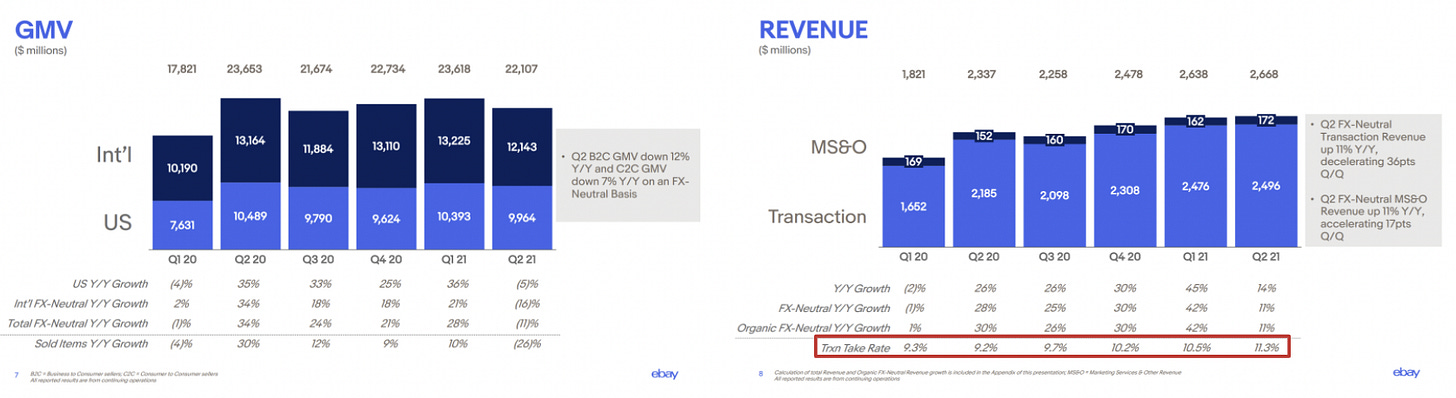

The company acts as a market maker, connecting buyers and sellers, and taking a cut of each transaction (gross merchandise value or GMV) flowing through its platform. The fee is based on the final price of the good. Initially, these fees were 5% below $25 and 2.5% above $25. Over time, eBay added listing fees and other seller services like advertising, increasing its take rate.

This wasn’t a new business model. Auction houses had been using it for hundreds of years. What was new was the scale. The internet enabled a global playing field.

E-commerce companies are divided into two camps: asset light marketplaces like Airbnb, eBay, and Etsy, and capital intensive businesses like Amazon, Carvana, and ThredUp. The major difference between the two are whether or not a company owns inventory and distribution. Both models work, but they require different levels of capital expenditure and result in different P&L dynamics.

eBay was the original asset light online marketplace. It didn’t own inventory or distribution and consequently enjoyed gross margins of 80% or more. Amazon is the opposite. It owns a sprawling distribution and fulfillment network, including a fleet of trucks and airplanes and an army of workers. It also owns inventory1. The tradeoff between the two approaches is control and customer experience. Because Amazon owns distribution and logistics, it can offer one- or two-day shipping to Prime members and a consistent fulfillment experience. In contrast, eBay’s sellers are responsible for shipping and the experience is far from unified.

Despite strong growth and consistent profitability, eBay struggled to attract investors. A business model based on strangers transacting with other strangers was perceived as just too weird. While laughable in hindsight, in 1995, only 8% of Americans were comfortable buying something online with a credit card, according to the Pew Research Center.

The history of tech is littered with similar objections. For Airbnb: who wants to stay in a stranger's house? For Uber: who wants to get into a stranger’s car? Perhaps we’re seeing the same thing with NFTs today: who wants to pay for a GIF? Eventually, Benchmark came around, investing $5M in the company for a 21.5% stake in June 1997. eBay didn’t need the money to fund its operations, but the investment bolstered its credibility.

The Million Auction March

Community was always an important component of eBay. Feedback forums and message boards were features from day one, serving as a place for far-flung collectors to gather, talk shop, and blow off steam. eBay carefully nurtured its community, often including member’s feedback into policy and product decisions. Riots erupted when it failed to do so. For example, when the company changed the color of feedback forum stars without consulting the community.

All companies change as they grow. Post-IPO, a number of vocal community members disapproved of the company’s direction, believing that management’s focus had shifted from improving the marketplace to increasing the share price. A grassroots movement called the Million Auction March formed in response. The movement’s logic was that eBay wouldn’t improve unless it had a strong competitor and the way to forge a strong competitor was for sellers to take their listings elsewhere.

The Million Auction March put a dent in eBay’s growth. From March through September 2000, listings count was flat. During the same period, Yahoo added nearly one million new listings. However, the protestors' success was short-lived and the movement ultimately failed to create a strong alternative.

Despite the Million Auction March, eBay still housed more buyers, more sellers, and more auctions than its competitors. Like a magnet, it eventually drew the dissenting sellers back. Sales put food on the table and eBay, with its strong network effect, had the most liquidity and generated the most sales.

eBay’s management understood the value of its network effect and how quickly fortunes could shift online, and responded swiftly to competitive threats. For example, in 1999, eBay sued Bidder’s Edge, a meta search site (think: TripAdvisor) that aggregated listings across online auction platforms. eBay alleged that the company trespassed, violated its copyright and trademarks, and slowed down site performance. When the lawsuit was filed, Bidder’s Edge had seven million listings compared to eBay’s four million. Scale begets scale for online marketplaces. Because sellers want to be where the buyers are, and buyers want to be where the sellers are, Bidder’s Edge posed a strategic threat. eBay won the suit and Bidder’s Edge folded as its business model became unviable after it was barred from scrapping eBay2.

The Bidder’s Edge lawsuit foreshadowed the measures tech platforms would take to protect their network effects, a situation playing out today on a larger scale. Similarly, the Million Auction March parallels the short-lived social media advertising boycott in the summer of 2020. Like the Million Auction March organizers, Facebook’s advertisers eventually crawled back because Facebook was where the performance was. For auctioneers and online marketers, performance ultimately trumped philosophy.

Beemers vs. Beanie Babies

One of the first items listed on eBay was a 1952 Silver Dawn Rolls Royce. Despite this, the conventional wisdom at the time was that cars would never sell online. Initially, eBay leaned into antiques and collectibles. Items like Beanie Babies were the killer app: they were lightweight, easy to ship, and relatively inexpensive (bubbles aside). That made them a low risk way for shoppers to dip their toe into e-commerce. In contrast, cars are heavy, cumbersome to transport, and expensive.

eBay’s attitude towards cars changed after it went public in September 1998. It now had to issue a quarterly report card to the market with its insatiable appetite for growth. Because eBay takes a cut of the final sales price (final value fees), increasing average selling prices boosts revenue growth. It takes a lot of Beanie Babies and Pez dispensers to move the needle. Gradually, eBay’s strategy shifted from emphasizing collectables - which drove its early growth - to more practical items with higher selling prices, including used cars.

Cars fit squarely within eBay’s right-to-win. The company succeeds in markets with passionate buyers and where existing sales channels were flawed, which was the case for used cars. Because of the differences between selling a BMW and selling a Beanie Baby, the company built eBay Motors, a separate marketplace for used cars, which launched in April 2000.

The unit economics of online used car sales ended up being favorable versus dealerships. Offline, used car dealerships bake a substantial sales commission into their prices. By comparison, eBay’s final value fee was lower, meaning that even after including shipping costs, buyers could save money buying online. Around 75% of the cars purchased on eBay were shipped to another state.

Used cars are another example of conventional wisdom proved wrong, highlighting the need to test assumptions. In the fourth quarter of 2019, eBay had cumulatively sold over seven million used cars, with a car selling on average every three minutes in 2019, equating to about 175,000 for the year3. Additionally, eBay Motors created a market for Carvana and other e-commerce businesses that came after it. Not bad for a category that would never sell online.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers. ❤️

For more like this once a week, consider subscribing. ❤️

More Good Reads

This note is based on Adam Cohen’s book, The Perfect Store: Inside eBay. If you’re interested in my book notes, give me a shout. Happy to share a Google doc with you. Kevin Kwon on underutilized fixed assets. Below the Line on the great Beanie Baby bubble.

Disclosure: This post contains an Amazon affiliate link to Adam Cohen’s book, from time to time we’ll discuss a book and include an Amazon affiliate link. If you’re interested in the book and purchase through the link, Jeff Bezos throws a few pennies in my direction. The author also owns shares of Facebook.

Amazon’s e-commerce marketplace is becoming increasingly reliant on third-party merchants. Over the years, the mix of third party sales on the marketplace has increased. Similar to eBay, Amazon charges third-parties a commission on platform sales. It also charges them for using Amazon’s logistics and fulfillment capabilities.

CNet, Bidder's Edge pushes Web site over cliff, January 2, 2002.

eBay, eBay Inc. Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2019 Results, January 28, 2020.