Hi 👋 - Bogged down in earnings season, so turning to the archives this week. Failure is a great teacher. In late November 2021, mattress-in-a-box firm Casper announced that it was being taken private at a valuation roughly 25% of its last private funding round. Today, some lessons from Casper’s failure. Thanks for reading.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers. ❤️

For more like this once a week, consider subscribing. ❤️

Killing a Ghost

Things are getting spooky in direct-to-consumer (DTC) land. On November 15, 2021 Casper announced that it was being acquired by Durational Capital Management, a private equity firm that also owns Bojangles. Durational is taking Casper out at $6.90 a share, a $286 million valuation. While this is a healthy premium to where Casper recently traded (roughly $3-$4), it's a far cry from Casper’s IPO price of $12 per share in February 2020 or its last private valuation of $1.1 billion in March 20191. As part of the transaction, Casper CEO Philip Krim is being replaced by Emilie Arel, who is experienced at turning around distressed retailers. The transaction will mercifully let Casper restructure out of the public eye.

Coke Pepsi Challenge

There’s only one Casper, but there are 174 other bed-in-a-box companies. Purple, one of the 174, went public in 2018, providing a financial statement taste test. While the products are indistinguishable, the P&Ls aren’t. For every $1 of revenue Casper earns, it spends $1.20. In contrast, Purple is profitable.

Casper’s gross margins are a few percentage points higher than Purple’s. Higher gross margins means more capacity to invest in customer acquisition, research and development (R&D), and other growth initiatives. Additionally, Casper and Purple spend a similar amount on sales and marketing (S&M), roughly $0.30 for every $1 in revenue. So far, so good.

General and administrative (G&A) expenses are where the wheels fall off. Casper jams a lot into this bucket, including retail employees, store leases and operating costs, corporate functions like finance, HR, and IT, credit card processing fees, professional services, and R&D. Casper’s G&A is 30-35% of revenue, three times higher than Purple’s. The company makes Peloton like the Bundesbank. This is why Casper bleeds cash while Purple makes money.

Spending on S&M or R&D spurs growth. Spending on G&A doesn’t. G&A is all about keeping the lights on and the trains running on time. Finance, HR, and legal are important functions, but they're supporting actors. For a growth company, G&A is the first place where operating leverage should show up. It’s a good acid test for how a company treats expenses. Casper fails.

There are other red flags. Casper and Purple both generate sales through two channels: DTC and retail partnerships. DTC consists of direct e-commerce and retail sales while retail partnerships are sales through third parties. For example, Casper is sold at Amazon, Costco, and Target. A big difference between Casper and Purple are their retail footprints. In 2020, Casper operated 67 stores while Purple had nine. This increases Casper’s G&A. However, Casper and Purple have a similar overall DTC sales mix, suggesting that Purple has a bigger e-commerce business and has built a better mousetrap.

Expense management is boring, but important. It’s also cultural. Casper raised over $300 million from VCs while Purple raised $2 million. One company had to be frugal from the onset. The other didn’t. This is reflected in their respective P&Ls. Companies that don’t have a handle on expenses can lose the ability to control their own destiny, particularly if they don’t generate free cash flow. That’s something I saw firsthand at Etsy in 2017 and something that Casper just learned the hard way.

Surely You’re Joking

Every company wants a tech multiple. The higher your multiple, the more money you can raise for a given level of revenue or, in more sober times, profit. However, few companies have the economic characteristics of a true tech company.

In What is a Tech Company?, Stratechery author and Below the Line crush Ben Thompson lays out what makes software economics unique. Software creates ecosystems, has zero marginal costs, improves over time (compare the OS on your smartphone to your mattress or your pillow cases; one gets better over time, the other degrades), offers infinite leverage, and enables zero transaction costs. Because of the potentially massive return on investment (build once, sell infinitely), software business models can justify heavy upfront investment in R&D and S&M. High gross margins solve a lot of problems.

Casper’s S1 is littered with tech buzzwords2. For example:

We distribute our products through a flexible, multi-channel approach combining our direct-to-consumer channel, including our e-commerce platform and retail stores, with our retail partnerships. Our multi-channel approach enables us to meet consumers where they want to shop, servicing them throughout their entire purchase journey. We believe our channels are complementary and creates a synergistic “network effect” that increases sales as a whole.

Like software economics, network effects businesses are rare. Here’s another example:

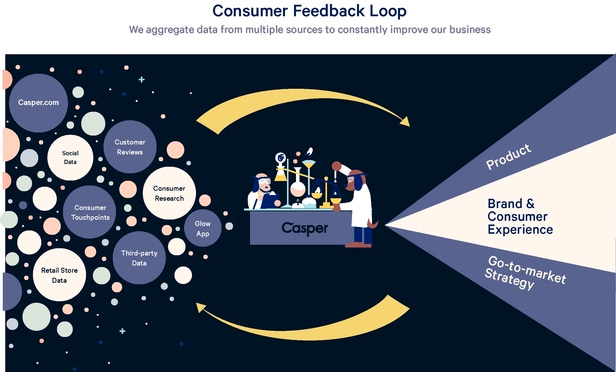

We believe that no other company catering to the Sleep Economy has our level of product development talent, resources, data-driven insights, or expertise.

There’s more, but between synergistic network effects, platform, and data-driven insights, we’ve already won buzzword bingo.

As Nobel prize winning physicists, polymath, and occasional pickup artist3 Richard Feynman said:

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.

S1 language aside, Casper’s business model contains none of the economic characteristics that make software so attractive: the company ships ninety-pound shrink wrapped mattresses. Brand building and storytelling are its strengths. It’s unclear if its management team believed its own spin (synergistic network effects!), or were just giving investors what they wanted to hear. Yet a company’s expense base and investment strategy should be dictated by the reality of its unit economics and competitive position. Everyone wants high gross margins and network effects. Few actually have them.

👻 👻 👻 Know someone with a Casper mattress? Or just a mattress?

The Limitations of TAM

In 2020, Casper’s sales were just shy of $500 million. While the company sells a variety of bedtime items like pillows, sheets, and a bedside glow lamp, sales are overwhelmingly mattresses.

Mattresses have a long replacement cycle and low purchase frequency. That’s a tricky way to build a business. You’re going to spend a lot of money acquiring a customer - if you don’t buy the keyword, one of the other 174 other mattress-in-a-box companies will - and if you see them again, it’ll likely be six or ten years down the road. At that point, you might need to pay to re-acquire them given short memories and dynamic competitors.

Product line expansion was a way to compensate for infrequent mattress purchases. Casper’s other products have shorter lifecycles, giving it the ability to cross-sell and improve purchase frequency. The S1 suggests this was its strategy:

From January 1, 2017 to September 30, 2019, we invested $27.7 million in research and development, and we expect to continue to invest in our product development capabilities in the future. We believe our rigorous approach to creating and improving our products has helped redefine and grow the addressable market that we call the Sleep Economy. This in turn offers consumers more opportunities to interact with us and purchase from us, which drives new consumer as well as repeat consumer business.

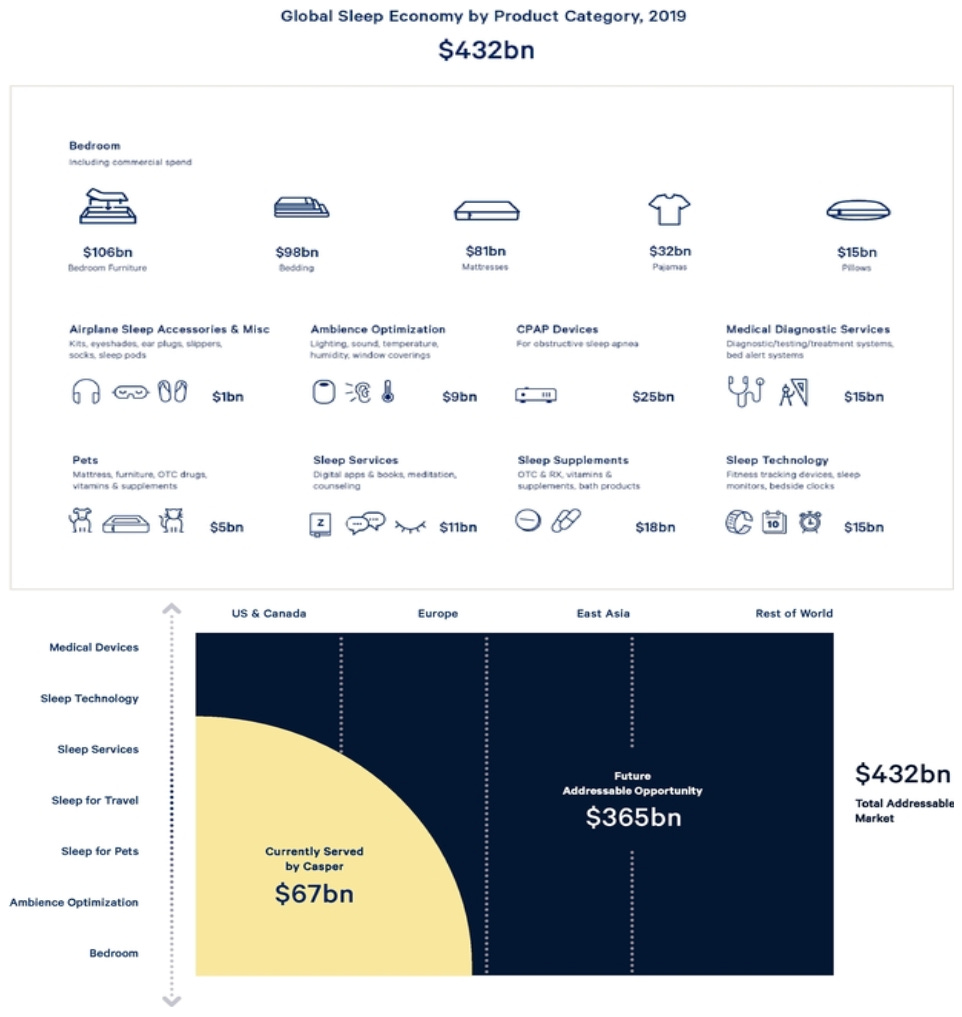

This is another area where Casper’s reality and story differ. From founding in April 2014 through September 2019, only 16% of customers purchased something other than a mattress, implying a low single-digit percentage per year. Yet Casper’s TAM definition was expansive4. According to its S1, it’s attacking the Sleep Economy, a $432 billion dollar opportunity including bedroom furniture, bedding, mattresses, jammies, pillows, and dog beds as well as some unexpected products like sleep supplements (!), sleep services like meditation, and counseling (!!), and medical diagnostic services (!!!):

A company set on winning a $432 billion market will behave and invest differently than a company focused on doing one small thing very well. As Bryne Hobart writes in his excellent teardown of Casper’s S1:

Casper is currently losing money, but that’s entirely consistent with its narrative. Its sales were $411 million in the last 12 months, and it estimates that the sleep economy is $432 billion. If you had a good business model and 0.1% market share, wouldn’t you grow at all costs, too?

Casper’s aspirations were bigger than its operational capabilities. Large TAMs are seductive, because they can breed giants like Amazon or Google. However, large markets also attract lots of competition. There were 174 other bed-in-a -box competitors, and that’s in just one part of the Sleep Economy.

A less sexy but more sustainable alternative is to start small. Amazon started by just selling books. Focus on dominating a niche, particularly one without much competition, then ladder up. As Peter Thiel writes in Zero to One5:

Every startup is small at the start. Every monopoly dominates a large share of its market. Therefore, every startup should start with a very small market. Always err on the side of starting too small. The reason is simple: it’s easier to dominate a small market than a large one. If you think your initial market might be too large, it almost certainly is...The perfect target market for a startup is a small group of particular people concentrated together and served by few or no competitors. Any big market is a bad choice, and a big marketing already served by competing companies is even worse.

No SPACs in a Foxhole

Focus matters. Under ideal circumstances, a business selling a product with low purchase frequency and high competition needs to execute well to succeed. 2020 and 2021 have not been ideal. First, Covid-19 shuttering Casper’s retail stores. Next, supply chain disruptions and inflation impacted its ability to meet demand and threatened its solvency. Yet while the company was sputtering, CEO Philip Krim was distracted. Krim is currently on the leadership team of three SPACs: Tailwind Acquisition Corp, Tailwind Two Acquisition Corp, Tailwind International Acquisition Corp. Even before the SPACs, Casper seemed more focused on brand building and storytelling than operations. Part-time CEOs don’t work well at struggling companies, just ask Twitter.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers. ❤️

For more like this once a week, consider subscribing. ❤️

More Good Reads

Petition on Casper crapping out. Ben Thompson on what is a tech company? Bryne Hobart on Casper’s S1. Below the Line on Casper and the dangers of yogababble.

Reuters, Mattress seller Casper's IPO slashes valuation by more than half, February 5, 2020.

Casper is by no means alone here. Recent S1s from DTC brands AllBirds and Warby Parker have had similar language. You can’t blame these companies for trying. Their objective with an S1 is to put the best possible foot forward within the confines of what the SEC says is allowable. Investors need to apply diligence and skepticism.

For details, check out the book Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!

To be fair, generous TAM definitions are becoming the norm. For example, Uber defined its mobility (rideshare) TAM in its S1 as $5.7 trillion, a cool 25% of US GDP: “TAM: Our Personal Mobility TAM consists of 11.9 trillion miles per year, representing an estimated $5.7 trillion market opportunity in 175 countries. We include all passenger vehicle miles and all public transportation miles in all countries globally in our TAM, including those we have yet to enter, except for the 20 countries that we address through our ownership positions in our minority-owned affiliates, over which we have no operational control other than approval rights with respect to certain material corporate actions. We estimate that these 20 countries represent an additional estimated market opportunity of approximately $0.5 trillion.”

Another point from Zero to One that’s relevant to Casper: “Beginning with brand rather than substance is dangerous.”