Hi 👋 - For growth companies, General & Administrative expenses like accounting and human resources aren’t sexy. But they matter. A look at Peloton’s expenses. Thanks for reading.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers. ❤️

For more like this once a week, consider subscribing. ❤️

Jimmy McMillan had a point. Just one. The rent is too damn high.

McMillan founded the Rent Is Too Damn High party and ran for mayor of New York City in 2005 and 2009 and governor of New York state in 2010. While his bids were unsuccessful - McMillan never won more than 1% of the vote - he succeeded in going viral, spawning memes and even a music video.

McMillan retired from politics in December 2015, so he’s probably never seen Peloton’s income statement. If he did, he’d have a second point:

Peloton’s P&L

Over the past five years1, Peloton has grown sales from $218M to $4.0B, nearly 20x. Over this span, net income deteriorated slightly from a loss of $71M to a loss of $189M. The company has generated positive adjusted EBITDA, a less stringent profitability metric popular in tech that excludes expenses like stock-based compensation, depreciation and amortization, and one-off items like recall expenses2.

It’s no surprise that a hyper-growth company is losing money. Growth today, profitability tomorrow is the Silicon Valley mantra. However, peek under the covers and Peloton’s expenses raise eyebrows.

The company’s major expense buckets are:

Cost of Revenue (COR or GOGS): Generically, these are the expenses required to manufacture and deliver a product or service to a customer. Peloton’s cost of revenue is divided between Connected Fitness Products and Subscription.

Connected Fitness Products Cost of Revenue: This line item includes the cost of building Peloton’s hardware - Bike, Bike+, and Tread - and delivering it to customers. This consists of materials, manufacturing, shipping and handling, warehousing, warranty and service costs, and fulfillment. Recently, this area has been under pressure from the recall of Peloton’s treadmill and elevated shipping costs.

Subscription Cost of Revenue: The cost of content creation and streaming expenses. This bucket is split roughly 50/50 between fixed costs like studio rent and instructor and production personnel expenses, and variable expenses, like music royalty fees and payment processing fees on monthly subscriptions.

Sales & Marketing (S&M): Expenses to increase brand awareness and purchase intent for Peloton’s hardware and digital subscriptions. This is composed of performance marketing media spend, asset creation, brand media spend, and expenses for retail showrooms.

General & Administrative (G&A): G&A is the least sexy expense bucket. This is where the bean counters sit. G&A includes accounting, finance, human resources, investor relations, and legal expenses3. For Peloton, it also includes executives and their not insignificant stock-based compensation (SBC).

Research & Development (R&D): Expenses, principally headcount, for projects focused on improving existing products and launching new products and features, both hardware and software. This is where engineers and product designers live.

What Drives Growth?

When looking at a P&L, two important questions are:

What investments (or expenses) drive growth?

Where will operating leverage come from? Another way of saying this is, what expenses should grow slower than revenue over time? An important consideration here is a business’s mix of fixed versus variable costs (more on that here).

By definition, Sales & Marketing investments drive growth by increasing purchase intent and improving brand awareness. Research & Development is the same. By developing new products and improving existing ones, R&D spending helps to engage and retain existing customers and acquire new ones. Content drives growth too, just ask Disney or Netflix. Creating and streaming workouts is an important component of Peloton’s growth algorithm, and this effort shows up in Subscription Cost of Revenue. In order to sell a bike or treadmill, it needs to be manufactured and delivered; that’s the purview of Connected Fitness Cost of Revenue.

That leaves Steve in accounting as the odd man out. Sorry, Steve. General & Administrative functions like accounts receivable and human resources are necessary to run a business, but don’t directly drive growth. Additionally, G&A is a prime candidate for operating leverage. For example, after achieving critical mass, an accounting team doesn’t need to double in size if revenue doubles. Viola, leverage.

Peloton is a _______ Company

For Peloton, G&A is where things get messy under the covers. A martian dropped down to earth and given Peloton’s income statement (poor martian!) could be forgiven for assuming that Peloton is a G&A driven company. While S&M expenses are larger in absolute terms, the past few years G&A expenses have seen the most incremental growth, particularly in FY-21.

One way to assess operating leverage is looking at the trajectory of expenses as a percentage of revenue. The charts below show Peloton’s General & Administrative expense as a percentage of revenue over the past five years. The company doesn’t screen well here, particularly when excluding stock-based compensation (right-hand chart). While scaled revenue nearly 20x during this period, the amount of G&A required to make a sale barely declined. This is, politely, hard to fathom.

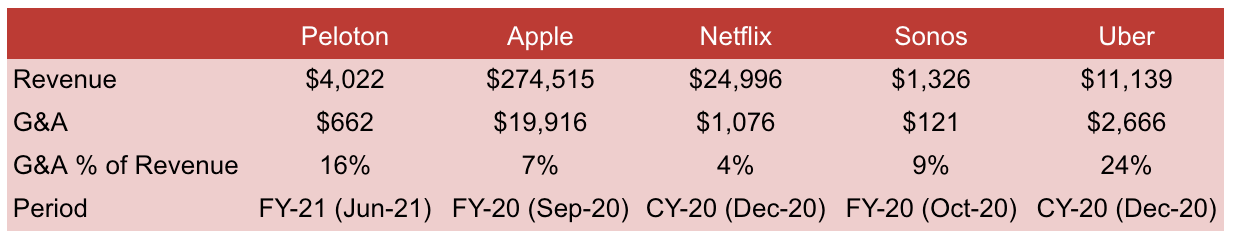

Peloton’s G&A as a percentage of revenue was 16% in fiscal year 2021, which ended in June 2021. For comparison, it was 4% at Netflix and 7% at Apple, two well-run, though by no means austere companies. Apple and Netflix are much larger than Peloton, so should benefit from more leverage. However, connected hardware maker Sonos puts Peloton to shame. In 2020, the company kept G&A to 9% of revenue on a significantly smaller revenue base. Peloton does screen better than Uber on this metric, though Uber is hardly a paragon of austerity.

Strength Training

A charitable take is that Peloton spent the past few years managing through hyper-growth, a global pandemic, and manufacturing and supply chain bottlenecks. Expense reduction wasn’t the priority. Glass half full: by reigning in expense growth in the future, particularly G&A, Peloton has plenty of room to improve profitability and generate more cash. Glass half empty: frugality is part of company culture, which is established early and hard to change. Peloton could be missing this gene; at minimum, it’s yet to develop the muscle. Not caring about expenses can have pernicious future effects.

In its June 2021 earnings report, Peloton disclosed that auditors had identified a material weakness in its internal controls around the identification and valuation of inventory. In other words, Steve in accounting has a problem. No company is perfect, but this is tough to swallow because Peloton has spent so much on G&A expenses. At minimum, it makes you question the efficacy of the spending. If you’re going to spend, make sure you’re spending well.

When Jimmy McMillan spoke to the voters of New York, he had a simple message: the rent is too damn high. I am a small Peloton shareholder, so won't ever get a meeting with its CEO and CFO. If I did, I’d bring a simple message of my own: your expenses are too damn high, do better. That one won’t get turned into a meme.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers. ❤️

For more like this once a week, consider subscribing. ❤️

More Good Reads

Blind Squirrel’s deep dive on Peloton. Below the Line on Peloton’s corporate wellness opportunity and the economics of digital fitness. Jimmy McMillan being Jimmy McMillan:

Disclosure: The author owns shares of Apple, Netflix, and Peloton.

Peloton reports on a fiscal year, which runs from July to June. The time period described above is from FY-17 to FY-21, spanning July 2016 through June 2021. Fiscal years are stupid. The world would be a better place if everyone used a calendar year.

Here’s Peloton’s reconciliation of net income to adjusted EBITDA from its FQ4-21 shareholder letter:

Having worked in FP&A, Investor Relations, and Strategic Finance, I have always been in this bucket.

Excellent article, Kevin. Fixed asset / inventory management is hard, especially for a hyper-growth company that didn't have a sound foundation to being with. It reminds me of Jason Fried's recent take on the distinction (philosophical) between the *company* and the *business*.

?