Hi 👋 - Everything old is new again. Many business models from the first dot-com bubble are getting a second chance right now. Today, a look at Webvan, a pioneer in online grocery delivery with a rapid ascent and an equally spectacular bust. Thanks for reading.

🛒 If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers.

🛒 For more like this once a week, consider subscribing.

Cash and Burn

Grocery is a tough business. So is delivery. E-commerce too. As Webvan discovered, combining the three doesn’t make anything easier.

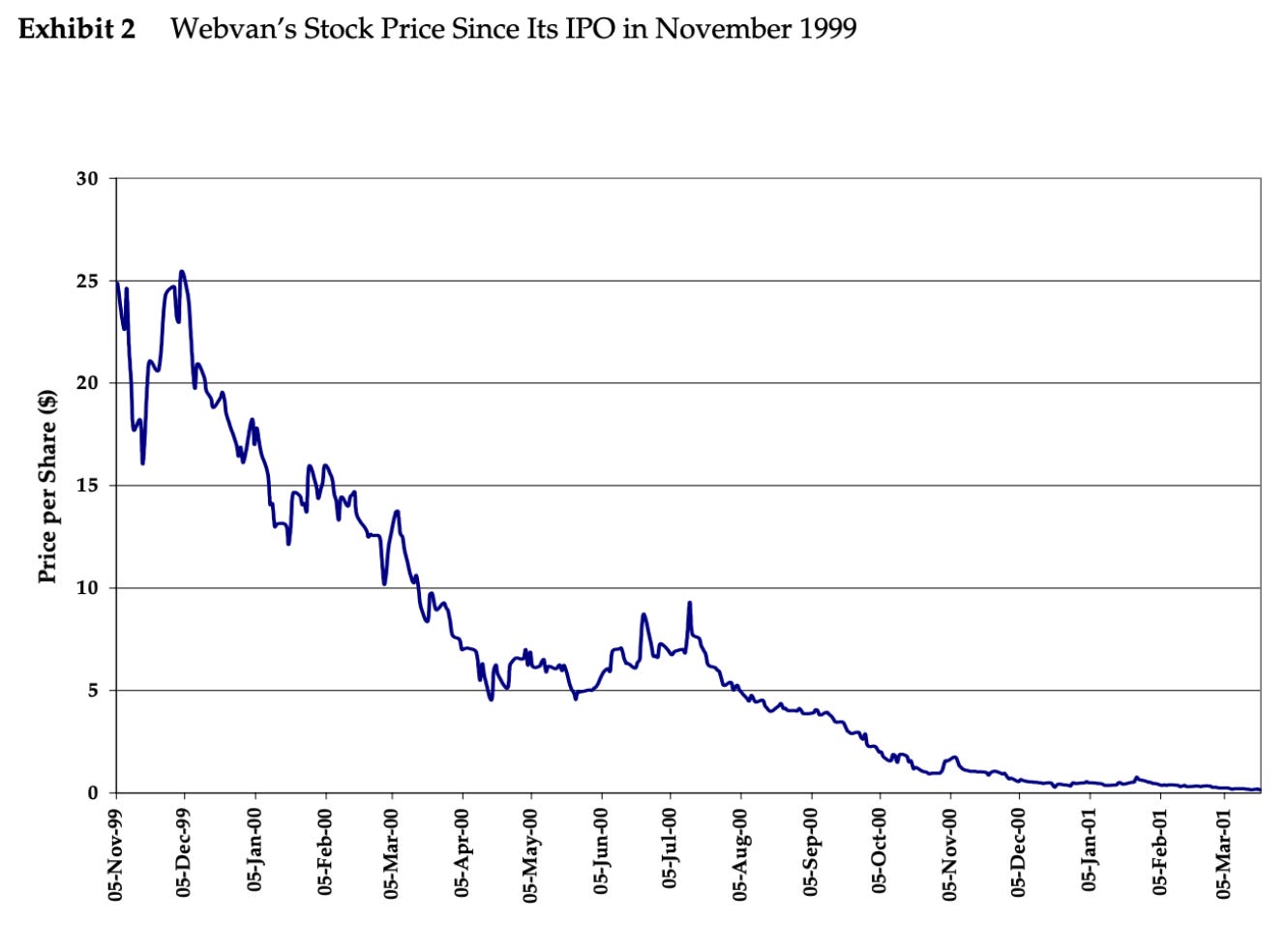

During the first dot-com bubble, Webvan was a high-flying grocery delivery startup. It raised $800 million from investors like Benchmark, Goldman Sachs, Sequoia, Softbank, and Yahoo (more impressive in 1999 than 2022) and went public in November 1999. At the time, cumulative revenue was $395,000. Analysts forecast sales mushrooming to $500 million in 20011, as Webvan captured significant share in a rapidly growing market.

The company ended its first day of trading with a valuation of $8 billion, about 40% of Kroger’s market cap. While investors were giddy, grocers were scratching their heads2:

Noting the company’s valuation, one Safeway executive whose company had a share price of $40 at that point, bristled, “They have the sales of two of our stores and one fourth of our market cap.”

His confusion wouldn’t last. Less than two years later, Webvan was bankrupt.

Webvan 101: Business Model

Entrepreneur Louis Borders founded Webvan in 1996 (he also started the eponymous bookstore chain). Borders’ wanted to leverage the internet to provide greater variety and better convenience than traditional supermarkets. To accomplish this, Webvan provided home delivery of groceries ordered online within a 30 minute window. Its target customers were dual-income families with little spare time.

For users, the economics were simple. Delivery was free on orders over $50 and $4.95 otherwise and there was no annual membership fee (for comparison, today Whole Foods charges $9.95 for delivery in a two hour window and $14.95 for delivery in a one hour window). Groceries were priced competitively with stores like Kroger and Safeway. Indeed, Webvan advertised prices 5% below mainstream supermarkets3. There’s a sniff test that a business can provide two of three: convenience, price, or quality. Webvan got greedy; it wanted all three.

The company’s strategy was to acquire customers with groceries, a high purchase frequency category, then ladder into additional items4:

The Webvan Group planned to begin by offering groceries which people shop for frequently to build critical mass, order frequency, and economies of scale. With an established customer base, it then planned to leverage its distribution system to expand to other categories, adding items such as consumer electronics and books whose profit margins were considerably greater than for groceries but were ordered less frequently. That is, they planned to attract an audience first and then “monetise those eyeballs” to bring in additional revenue and do this on a global scale.

It stumbled on the first rung.

Conveyor Belts and Humidors

Groceries are a low margin, high volume business. Home delivery added complexity. In particular, Webvan was burdened with two expenses that grocers don’t have: delivery and picking orders.

To offset these additional costs, it needed automation and scale. This would come from four areas. First, leveraging proprietary software to create scalable and replicable systems. Webvan claimed its operations needed one-third the employees of a supermarket5. Additionally, all facilities shared a single design to encourage economies of scale. Second, driving efficiency through automation. The employees (pickers) who fulfilled orders could process 450 items per hour and work on up to 16 orders simultaneously6. Third, using real-time data for inventory management to drive higher inventory turnover versus a grocery store. Fourth, locating operations in industrial areas where rents were cheaper than the commercial street where supermarkets are located.

These four elements came together at Webvan’s highly automated distribution centers (DCs). Each DC could carry 50,000 SKUs, fulfill 8,000 orders per day, and generate $100 million in revenue per year at full capacity (8,000 orders per day x ~$100 per order)7. Webvan invested heavily in their development. Each DC cost about $35 million to build and had the capacity of 18 supermarkets. A team of eighty software developers spent three years writing code to automate as much of the business as possible. For example, custom software determined the optimal picking plan for each order and the best route through the DC. Routes were optimized so that large, heavy items were packed first and more delicate items later. Orders could be tracked end-to-end through a proprietary barcode system. A custom inventory management system knew of the location of every SKU and how many items were at hand in a given DC in real-time. These systems and processes would (theoretically) enable the efficiency and scale required to make delivery economics work.

After years of development, Webvan launched grocery delivery in June 1999, with its first DC serving the San Francisco Bay Area from Oakland, California. The facility spanned 330,000 square feet and contained cooking facilities, multiple temperature zones, over five miles of conveyor belts, and a humidor lined with Spanish Cedar for cigars. Here’s what it looked like:

Why Webvan Failed

Webvan was a capital intensive business. A network of distribution centers, a fleet of delivery vans, and an army of software engineers weren’t cheap. Aggressive expansion plans compounded cash burn.

Within 18 months of launch, Webvan operated in nine markets8. As Bill Gates noted, automation isn’t automatically a good thing9:

The first rule of any technology used in a business is that automation applied to an efficient operation will magnify the efficiency. The second is that automation applied to an inefficient operation will magnify the inefficiency.

The same is true with expansion. A corollary to Gate’s axiom is that expanding a cash generating operation magnifies cash flow. However, expanding a cash burning operation magnifies cash burn. Unfortunately, Webvan never proved the economics before scaling.

According to management projections, at 100% utilization, DCs would generate 12% operating margins, about three times the grocery industry average. To breakeven, DCs required 40-50% utilization. Additionally, management expected DCs to breakeven after five quarters. Webvan never got there on either count. Throughout 1999 and 2000, DC utilization was stuck at 25-30% and the Bay Area DC never broke-even10.

Webvan’s model worked at scale (on spreadsheets, anyway), but as Corry Wang points out, getting to scale required the kindness of strangers. While the company was busy burning cash, the dot-com bubble burst. As the pendulum swung from greed to fear, investors no longer wanted to fund cash burning internet businesses.

Webvan was default dead when the clock struck midnight and ran out of cash before it could generate enough demand to cover its fixed costs and customer acquisition costs (CAC). Multiple factors were at play here, including:

Low Internet Penetration: While smartphones and internet penetration are ubiquitous today, that wasn’t the case in 1999. Similarly, e-commerce was a novelty. According to the Pew Research Center, in 1995 only 8% of Americans were comfortable buying something online with a credit card. Adoption was growing quickly, but off of a low base. In contrast, the weekly trip to the grocery store was an ingrained consumer behavior.

High CAC: The usual suspect had its fingers all over the crime scene as well. CAC increased from $129 in Q3 2000 to $166 in Q4 200011.

Low Retention: Retention was another struggle. In the Bay Area, only 50% of the customers who tried Webvan ever placed a second order12.

Pricing: Grocery store layouts (milk in the back) create multiple opportunities for upsell. Milk is priced as a loss leader to get people to walk through the store. Webvan offered low milk prices without having the upsell opportunity13. It’s worth noting that no Webvan executives had prior grocery industry experience.

Low Delivery Density: For delivery economics to work, route density needs to be high. Delivery costs fluctuate based on the number of drops a driver can make per hour. The higher, the better. Mean travel time between stops is a critical variable14. At full capacity, delivery drivers were expected to make four to six drops per hour. In actuality, analysts estimate that they were making three or fewer. As losses mounted, Webvan expanded its delivery windows from 30 minutes to 60 minutes, but by this time, this was rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

The Lessons of History

As Getir, GoPuff, Gorillas, JOKR and others show, many business ideas from the first dot-com bubble are getting a second chance. While internet adoption and e-commerce penetration are much higher today, the economics of online grocery delivery are still challenging.

Webvan’s failure provides a number of lessons for investors and operators:

Digital ≠ Physical: Atoms are harder than bits. Apples bruise, berries squish, and meat spoils. Just think of the difference between how long Google Maps says a trip will take and how long the trip actually takes (traffic jams, accidents, street sweepers, someone pulling the emergency brake on the C train as you’re pulling out of the West 4th Street station). This adds an element to risk and unpredictability for any business where a key metric is the number of deliveries per hour.

Default Dead vs. Default Alive: Survival is a precondition for growth. A business that can achieve profitability with its current expense base and growth trajectory is default alive. A business that can’t is default dead. Webvan was the later. Its model could have worked at scale, but it didn’t have the runway to get there. Markets are cyclical. Future investments are never guaranteed. When psychology shifts, a sexy startup can turn into a pumpkin.

Beware of Leaky Buckets: Webvan calculated that it needed 1-3% penetration of its target market to be viable. While 6.5% of Bay Area households tried Webvan, only half of them ever placed a second order. Unless first order economics are world-class, low retention combined with high fixed costs is a troublesome combination. Retention is critical. Like Webvan, there’s mounting evidence that the recent crop of instant grocery delivery services are struggling with retention. Watch out below.

Premature Scaling: Scaling a money losing business magnified losses. Webvan never proved its economic model in one market before expanding into new geographies15:

Webvan “committed the cardinal sin of retail, which is to expand into a new territory - in our case several territories - before we had demonstrated success in the first market,” said Mike Moritz, a Webvan board member and partner at Sequoia Capital, one of the company’s venture capital backers. “In fact, we were busy demonstrating failure in the Bay Area market while we expanded into other regions.”

Positive Constraints: Automation and expansion aren’t always good. Constraints aren’t always bad. Webvan operated at the metro area level. A smaller playing field might have been better. For example, delivery was profitable in high-density San Francisco, but unprofitable in the suburbs16. Initially focusing on specific neighborhoods could have built route density. Today’s crop of grocery delivery start-ups focus on neighborhoods versus whole metro areas, so they seem to have learned this lesson.

Another lesson from history is that we don’t always learn from history. Webvan was the first online grocery delivery service to go belly up. It won’t be the last.

🛒 If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers.

🛒 For more like this once a week, consider subscribing.

More Good Reads

Corry Wang’s Twitter thread on the economics of Webvan. The Product Failures podcast on why Webvan failed. Reuters on what Amazon learned from Webvan. Below the Line on how to survive a downturn.

Deighton, John A., and Kayla Bakshi. "Webvan: Groceries on the Internet." Harvard Business School Case 500-052, November 1999. (Revised March 2003.)

Deighton, John A., and Kayla Bakshi. "Webvan: Groceries on the Internet." Harvard Business School Case 500-052, November 1999. (Revised March 2003.)

Deighton, John A., and Kayla Bakshi. "Webvan: Groceries on the Internet." Harvard Business School Case 500-052, November 1999. (Revised March 2003.)

Deighton, John A., and Kayla Bakshi. "Webvan: Groceries on the Internet." Harvard Business School Case 500-052, November 1999. (Revised March 2003.)

Deighton, John A., and Kayla Bakshi. "Webvan: Groceries on the Internet." Harvard Business School Case 500-052, November 1999. (Revised March 2003.)

Deighton, John A., and Kayla Bakshi. "Webvan: Groceries on the Internet." Harvard Business School Case 500-052, November 1999. (Revised March 2003.)

Deighton, John A., and Kayla Bakshi. "Webvan: Groceries on the Internet." Harvard Business School Case 500-052, November 1999. (Revised March 2003.)

Reuters, From the ashes of Webvan, Amazon builds a grocery business, June 18, 2013.

Deighton, John A., and Kayla Bakshi. "Webvan: Groceries on the Internet." Harvard Business School Case 500-052, November 1999. (Revised March 2003.)

Deighton, John A., and Kayla Bakshi. "Webvan: Groceries on the Internet." Harvard Business School Case 500-052, November 1999. (Revised March 2003.)

Deighton, John A., and Kayla Bakshi. "Webvan: Groceries on the Internet." Harvard Business School Case 500-052, November 1999. (Revised March 2003.)

Product Failures from Rocketship.fm, Product Failures: Webvan, January 2020.

Reuters, From the ashes of Webvan, Amazon builds a grocery business, June 18, 2013.

Reuters, From the ashes of Webvan, Amazon builds a grocery business, June 18, 2013.

Reuters, From the ashes of Webvan, Amazon builds a grocery business, June 18, 2013.