#97 - Sweetgreen vs. DoorDash

A Love-Hate Relationship

Hi 👋 - Sweetgreen’s S1 reveals just how difficult it is to compete against aggregators like DoorDash and Uber Eats. Today, a look at the power delivery marketplaces and how restaurants like Sweetgreen are fighting back. Thanks for reading.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers. ❤️

Unlike Sweetgreen, Below The Line is free. 🥗

Existential Threats

Sweetgreen is a thoughtful company. It prioritizes sourcing produce from local, organic, and regenerative farms. It’s in tune with seasonality and mindful of its carbon footprint. Instead of managers, it has assistant coaches and head coaches. Flooded with sunlight and filled with succulents, its stores are Instagram worthy:

It's also conscious of how it sells its salads. The company is skeptical of delivery marketplaces like DoorDash, Grubhub, and Uber Eats and favors direct channels like its website and app. Jonathan Neman, Sweetgreen’s co-founder and CEO sees delivery marketplaces as an existential threat1:

The question is going to be, how many of those restaurants have direct relationships, versus marketplace relationships? Which is in my opinion, the greatest existential risks facing our industry, reminiscent of...Nike versus Amazon, Disney versus Netflix, Four Seasons versus Expedia. It's a very similar story of whoever owns the customer extracts more value in that value chain. And I think that's been a huge focus for us. It has been for years.

Value accrues to whoever owns the customer and bad things happen when someone gets in between you and your customer (ask a hotelier what they think about Booking.com). Sweetgreen is cognizant of this threat. Twenty-five of the eight-five mentions of “marketplace” in the S1 occur in the risk section. For example2:

These food delivery marketplaces own the customer data for sweetgreen orders placed on such marketplaces and may use such customer data to encourage these customers to order from other restaurants on their marketplaces.

Despite the disintermediation risk, the S1 also reveals that Sweetgreen is increasingly reliant on delivery marketplaces. Competing with aggregators3 is hard.

DoorDash, The Gateway Drug?

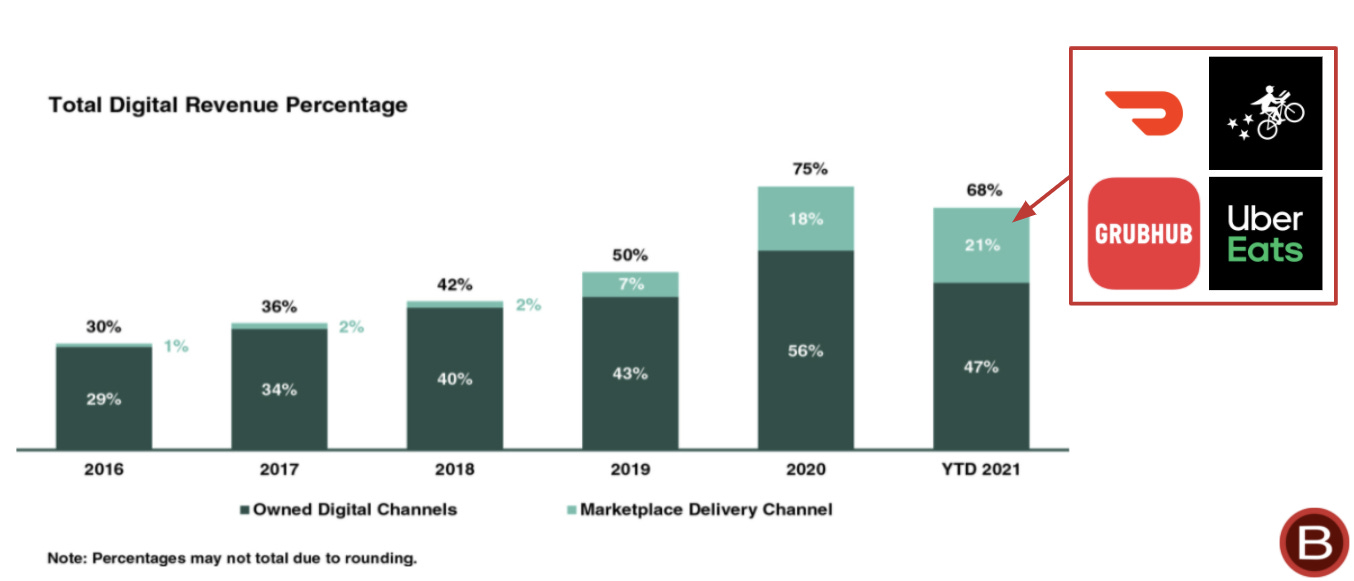

Investing in technology is a priority for Sweetgreen4. It embraced apps and digital ordering early. Today, all 140 of its restaurants offer delivery. These technology investments are paying off. Digital channels have grown from thirty percent of sales in 2016 to sixty-eight percent of sales in 20215. Digital channels are split into two buckets:

Owned Digital Channels: Delivery, pick-up, or Outpost orders placed through Sweetgreen’s app or website, and, charitably, in-store transactions that are consummated via digital scan-to-pay feature in the app. Delivery and Outpost orders are fulfilled by Uber Eats.

Marketplace Delivery Channel: Delivery or pick-up orders made through third parties like DoorDash, Grubhub, Postmates, and Uber Eats.

Recently, Sweetgreen’s growth has become more reliant on the channels it fears the most. Marketplace delivery mix has tripled from seven percent of sales in 2019 to twenty-one percent of sales in 2021. Revenue through owned digital channels declined almost ten percentage points, from fifty-six percent in 2020 to forty-seven percent in 2021, suggesting that marketplace delivery is cannibalizing some of Sweetgreen’s direct digital channels. That’s a worrying trend.

In absolute dollars, marketplace delivery sales increased $21 million in 2020 compared to growth of less than $7 million for owned digital channels. Through the end of September 2021, the same figures are more balanced: $25 million and $22 million respectively.

There are two major factors at play here. The first is Covid-19, which shuttered offices and forced restaurants to lean into takeout and delivery. The second, somewhat related, is the continued adoption of services like DoorDash and Uber Eats which was accelerated by the pandemic, but started beforehand.

As marketplace delivery mix increases, so does the wedge between Sweetgreen and its customers. Whoever owns contact information and payment details controls the ability to re-market and re-sell to customers. DoorDash and Uber Eats want GMV, they don’t care where it comes from. They’re happy to deliver a Super Green Goddess salad from Sweetgreen, but they’re equally happy to deliver a salad from Chop’t, a burrito from Chipotle, roast vegetables from Dig Inn, or any item from the hundreds of thousands of restaurants on their marketplaces. Furthermore, delivery marketplaces will gladly serve ads from competing salad chains to existing Sweetgreen customers. In contrast, Sweetgreen very much cares that customers order salads from Sweetgreen. This is why Jonathan Neman is worried about marketplaces.

Have a friend who likes Sweetgreen? 🥗

Channel Economics: Theory vs. Practice

Sweetgreen doesn’t deliver orders itself. It uses third parties to fulfill orders through its owned digital channels, so it pays delivery fees for both native delivery, orders placed through its app and website, and marketplace delivery. Delivery fees are becoming a material expense. In 2021, they were $13.4 million, or roughly six percent of revenue, compared to $11.9 million, or four percent of revenue in 2020. Restaurant operating margins range from ten percent to twenty percent6, meaning that delivery fees could eat up a quarter to a half of Sweetgreen’s potential profits.

In theory, direct digital orders should be Sweetgreen’s most profitable. Native digital customers have the highest order frequency and average order value twenty-one percent higher than in-store transactions paid for with cash or credit card7. One of the surprises of Sweetgreen’s S1 is that in practice this isn’t the case. That’s because the company offered promotions and discounts on native delivery. There are good reasons for doing this. For example, having stored credit card information is a boon to conversion (see: Apple Pay). Sweetgreen would much rather have customers order directly than from DoorDash. However, promotion is a risky tactic when your competitors have more cash and the ability to cross-sell thousands of different restaurants.

Sweetgreen expects owned digital profitability to improve over time as promotional activity tapers and it changes its native delivery partner. It launched native delivery in 2019 with Uber Eats as its exclusive partner, but is transitioning to DoorDash, where it negotiated better terms. DoorDash will get a fixed fee per order based on geography and mileage. In contrast, Uber Eats got a flat fee plus a commission percentage on each order. Moving from Uber Eats to DoorDash should reduce delivery fees as a percentage of revenue and make native delivery expenses less variable, which is a smart move. The transition shows that Sweetgreen has some leverage with aggregators.

For both native digital and marketplace channels, Sweetgreen expects to negotiate lower commissions and fees as it scales. As the company enters the public markets, the evolution of owned digital channels versus marketplace delivery will have implications for its capital efficiency, P&L, and stock performance.

Tactics For Competing With Aggregators

Relative to brands, aggregators have advantages in customer acquisition and marketplace liquidity. You can order Sweetgreen salads on DoorDash, but you can also order Asian noodles, burritos, and Chinese food. The reverse isn’t true. But brands aren’t helpless. There are plenty of salad chains, but there’s only one Sweetgreen. Similar to airlines and hotels, restaurants are developing playbooks to encourage direct ordering. The S1 highlights Sweetgreen’s tactics, including:

Pricing: Owned digital channels typically have lower menu prices compared to marketplaces. Sweetgreen wants customers ordering directly to get the best value8.

Menu Exclusivity: Select dishes are only available through owned digital channels. Some seasonal menu items are not listed on third-party marketplaces.

Promotions: Sweetgreen offers promotions and discounts for direct orders.

UX: The company strives to make direct channels the best ordering experience, like saving a customer’s favorite order.

Maintaining direct customer relationships on owned digital channels is a key strategic goal for Sweetgreen. The S1 shows that aggregators have a gravitational pull that’s difficult to overcome. As a public company, Sweetgreen will offer a quarterly view into the battle between brands and aggregators.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers. ❤️

Unlike Sweetgreen, Below The Line is free. 🥗

More Good Reads

Sweetgreen co-founder and CEO Jonathan Neman on building the modern restaurant. The Wall Street Journal on how restaurants are using pricing and other tactics to compete with delivery marketplaces. Below the Line on the battle between brands and aggregators and booking a hotel room in Secaucus, New Jersey.

Founders Field Guide, Jonathan Neman - Building the Modern Restaurant, March 11, 2021.

I’ll use aggregators and marketplace delivery interchangeably. Both refer to companies like DoorDash and Uber Eats.

2021 numbers refer to results through September 26, 2021. For simplicity, I’ll refer to them as 2021.

Founders Field Guide, Jonathan Neman - Building the Modern Restaurant, March 11, 2021.

Sweetgreen S1 as filed with the SEC on October 25, 2021.

I wonder how much this tactic matters. If you’re ordering a $15 salad, you probably aren’t terribly price conscious. Convenience and ease of ordering probably matter more than price.